How to Organize Your LEGO Parts Collection, Part 1: Organizing Strategies and Constraints

/Today’s guest article comes from Elisa Triffleman on behalf of ILUGNY about ways of organizing a LEGO parts collection. This article is the first in a three-part series about organization, sorting and storing LEGO.

LEGO parts can sometimes become unwieldy as collections grow, so how do you organize everything? This article will explore your many options, but if you want the TLDR summary, the best system for organizing LEGO parts is one that best fits your needs as a builder at any given point in time.

The members of ILUGNY recommend you first read Tom Alphin’s excellent, comprehensive (and free!) analysis of LEGO-related organizational and storage strategies. Alphin’s guide is partly about organizing children’s LEGO and draws on the experiences of a broad array of individuals. Our series of articles focuses solely on the organizational needs of adults who have LEGO elements for their own use and represents a consensus of the adult LEGO Users Group, ILUGNY. Bear in mind that whatever strategy you decide on could change over time as you go along as your needs and/or projects change.

Part 1 of this series focuses on the mental work of organizational strategies, starting with what your LEGO-related goals are, as this can be a way to identify workable strategies for dealing with that giant pile of LEGO pieces. We urge people to make realistic assessments of their space, time and budgetary constraints. Part 1 then discusses general organizational principles for dealing with LEGO pieces, baseplates and mosaic pieces.

In Part 2, we’ll talk about ILUGNY members’ practical tips for the physical operation of organizing LEGO parts and sets, including specific recommendations for sorting; shelving, containers and labeling; and how to keep track of your inventory. In Part 3, we’ll discuss how to organize, store and display minifigures and minifig-related parts.

Contents of a Collection

Because this is a longer deep dive, here is a table of contents with handy jump links to help you navigate the different sections of this article.

I. Introduction

II. How People Wind Up With Piles of LEGO

1. “Inheriting” LEGO

2. A Pile of Your Own Making

3. Set-Building and Ensuing Parts

III. Constraints: Budget, Space, Time and Temperament

IV. Organizing Strategies and Styles

1. Engineering Without Worrying About Conventional Visual Appeal

2. Engineering With Aesthetics

3. Artistic Endeavor Facilitated By Engineering

4. Selling Parts

5. The Mixed Approach

VI. Conclusion

I. Introduction

Recently, 24 members of the adults-only and New York-based LEGO Users Group ILUGNY reinvigorated a long-standing discussion about how to organize or re-organize our LEGO parts collections. The occasion for this revived conversation was that two long-standing members had changed their living spaces and so had an opportunity to consider how best to set things up anew. Around the same time, new members had joined the LUG who were either starting collections from the bottom up or had parts collections that were unorganized and not fully usable.

ILUGNY QR code, name and trees built by members at Google HQ in New York, July 2022; LEGO Statue of Liberty. Photo by author.

ILUGNY members are all Adult Fans of LEGO (AFOLs). The 40+ current members at the time of this writing live in Connecticut, New Jersey, downstate New York (from Orange and Dutchess Counties south to New York City and Long Island); Chicago, IL; and Jacksonville, FL. Some members also belong to multiple LUGs around the US. Most members emerged from their “dark ages” (the time period between playing with LEGO as children and renewed interest as an adult) a few years or decades before. Some had never stopped building. One had just started building with LEGO elements for the first time a few months before.

How the members use LEGO is somewhat varied. Many use them for building for display at small-scale events. Others display builds at larger LEGO-related fairs, conventions and other venues. Some also sell LEGO parts and sets. In these ways, ILUGNY members bring a variety of backgrounds to the topic of organizing LEGO elements, but it is fair to say that the group as a whole is committed to and has developed expertise in everything LEGO. Most have medium-sized to very large LEGO parts collections, and a few in very small spaces like a New York City apartment.

This series of articles is focused on organizing LEGO parts and pieces for adults and older teens. Organizing LEGO elements, like all organizing, is not a single topic. In fact, it’s a collection of issues, which is reflected in the various parts of this series.

In Part 1, we talk first about some of the common ways in which people wind up with enough LEGO pieces to require organizing them. We then move on to discuss some of the constraints on LEGO collections and organization, such as budget, space and time. Finally, we talk about general guiding principles or organizational strategies for LEGO elements, baseplates or large plates and ways to think about organizing LEGO for mosaic makers.

We’ve chosen not to address organizing LEGO sets in Part 1 because in our experience, organizing sets does not typically involve guiding principles or strategies to consider, but rather focuses on the practicalities of physically arranging them in a stable manner without damaging them and then inventorying them. Where organizing sets can necessitate guiding principles, we have found that keeping track of their parts is a more central problem.

In Part 2 of this series of articles coming soon, we’ll look at a variety of practical, concrete tips for the physical aspects of organizing pieces and sets, such as shortcuts for sorting and specific recommendations for shelving, containers and labeling. Part 2 will conclude with a review of how to keep track of your inventory so (hopefully) you don’t wind up with too many of one part and not enough of another. In Part 3 of this series, we deal with the issues around organizing, storing and displaying LEGO minifigures and parts.

minifig parts. Photo by D. Griffith.

No matter what your circumstances are or what kind of a LEGO collection you have, you should read Tom Alphin’s excellent, comprehensive and free organizational guide for detailed advice about organizing LEGO in various age groups, and for more information about a few of the strategies we talk about for adults in this series of articles.

That said, Part 1 of our series of articles covers instances of strategies that Alphin mentions but does not focus on. We also talk a little about the varying goals people have and some common styles of working with LEGO. Strategies for organizing LEGO building baseplates or large plates, and mosaics are also areas that Alphin does not address. We therefore think this article and the larger series adds to the foundation that Alphin’s guide provides.

The organizational issues for children under about 16 years old are somewhat different than those faced by adults and older teens and won’t be covered in our series of articles. However, since many ILUGNY members are parents, we sympathize with the need for having a system in which no one’s feet are impaled on a stud or a LEGO spear. As Alphin notes, an organizing system can be as simple as a box, bag, or container into which everything is thrown at the end of play.

II. How People Wind Up With Piles of LEGO

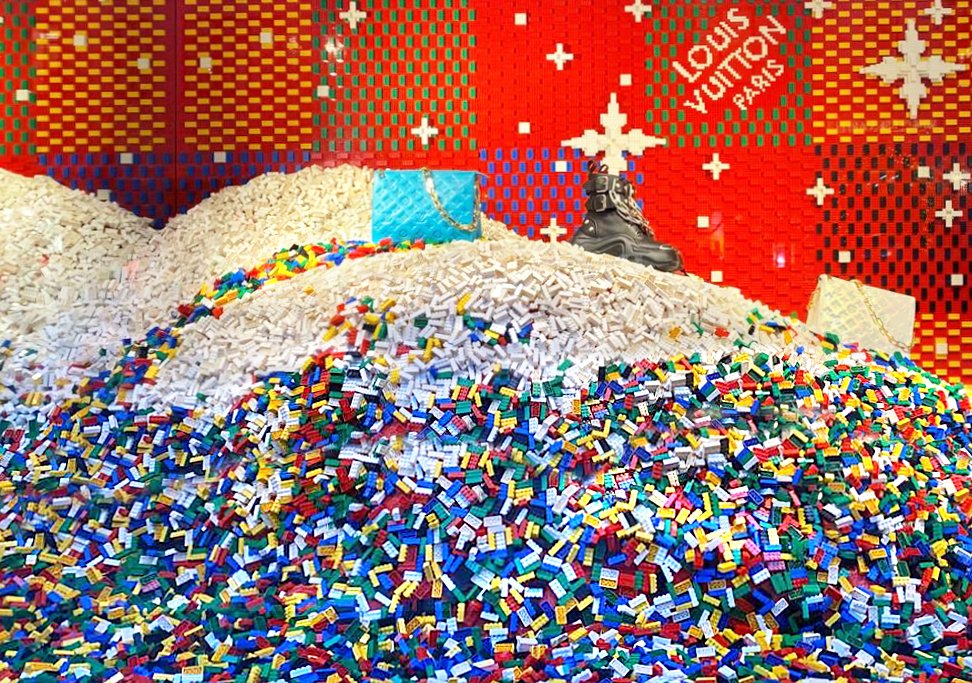

A ”fashionable” pile of LEGO. Photo by B. Probert, Louis Vuitton 5th Ave. store, NYC, December 2022.

It's worthwhile for adults with LEGO collections to take a moment and consider some of the many routes into developing collections. Thinking about these routes can help clarify goals for LEGO building and then guide the work of organizing the pieces. We recognize that many readers of this article and the broader series of articles are already clear about their goals. If this is the case for you, please skip to Section III: Constraints.

1. “Inheriting” LEGO parts

One route to being an adult with a LEGO collection is the incidental or accidental way. Perhaps some children you took care of have outgrown their love of LEGO (or have entered their dark ages) and have left a LEGO pile behind. As a result, you may now be thinking, “Now what do I do with this *#@% mess?” without having any other goal for what to do with the pile other than not tripping or hurting one’s feet, etc. If this is the case for you, consider doing something completely contradictory: stop thinking about organizing for a little while. Instead, sit and play with the LEGO pieces, just like kids do, and see what you come up with without judging the quality.

If after a couple of times doing that, you have no desire to go further, then sell them. Most yard sales with LEGO feature big tubs of unsorted LEGO pieces, a few sets, and maybe a few previously-cherished minifigures. You can also give your LEGO away - and there are many who will be very grateful in light of how expensive LEGO sets and parts are - but just realize that LEGO is a commodity like any other commodity. If you doubt this, please visit BrickLink or BrickEconomy for insight into just how much money flows around and through all types of LEGO pieces.

If at that point, you decide you want to enter the re-sale marketplace without wanting to build your own LEGO structure, then please skip to Section III: Constraints.

Mixed LEGO parts, ready for anything, including yard sales. Photo by author.

2. A Pile of Your Own Making

From a trip to the Pick-A-Brick Wall at the local LEGO retail store, awaiting sorting and organizing. Photo by author.

Speaking of yard sales, perhaps your route into having a LEGO collection came while looking at a bunch of LEGO at a yard sale or when you passed a LEGO store with or without a child in a mall and the sets and/or figures interested you. Maybe they brought back good memories or maybe you wished that you had played with them as a child. Or maybe you went to a LEGO retail store, saw the Pick-A-Brick wall, and were intrigued enough by all those nifty colors and shapes and their potential to have bought yourself a bunch of parts, and now you’ve got an unorganized pile.

Like our advice for people “inheriting” LEGO pieces from children, take a little time to sit and play before you try to organize. This could help you to think about what draws you currently to those LEGO bricks and what you might want to get out of them going forward. This in turn could point you to an organizing strategy.

Sometimes, though, yard sale LEGO bins will have chunks of partially disassembled sets without instructions or labeling. If you subsequently become curious about re-assembling the set(s) rather than dealing with the parts per se, you could first identify the set(s) using unique parts, minifigs, etc. on BrickLink and then use the set inventory list (available via BrickLink or LEGO.com for more recent sets) to find the remaining parts in the bin. This will also allow you to identify what elements are missing so you can replace them.

3. Set-Building and Ensuing Parts

One more way into having a collection of LEGO is via set-building – you’ve bought and built a bunch of sets, whether just for yourself or together with children or other adults. There are potentially at least three outcomes for this:

Pieces from the LEGO Black Panther set, ready to go back into the box… or not. Photo by author.

A. There are situations in which individuals solely want to be able to re-build one specific set in the exact same way as the original at a later date, and who either have no other goals for or interest in LEGO, or who know that those particular pieces won’t be used for anything other than repairing that particular set. In this instance, keeping all the set-related pieces together, separate from any other type of grouping, makes sense. There are a variety of containers you could use to do this, including the original box and some plastic baggies or a container or two. This need not be an involved process. You can also put the instruction books into a plastic bag to keep them legible and free from tears, stains, etc.

That said, while keeping all the parts from a given set together is often the way in which people start organizing their LEGO pieces, we generally advise against trying to keep LEGO set pieces together as a primary means of creating an organizing system. Outside of the limited situation of wanting to build or re-build a set exactly the same way, many adults who build MOCs may end up wanting to use pieces flexibly as needed. They therefore want to be able to find specific pieces from across a variety of sets without necessarily having to repeatedly sort out whatever piece they want at the moment from every other piece from a particular set.

B. There is the person who gets interested in LEGO via building sets and finds it has sparked their curiosity or their creative drive. You probably already know you want to keep building or doing something with your LEGO elements beyond the process of following instructions, but you’ve yet to evolve a specific area of interest or a specific goal for your building activities.

This is an instance in which the sequence of 1) developing goals and then 2) organizing the LEGO could go the opposite direction: the process of making organizing decisions might help you to clarify what your current interest area(s) are and what your priorities are, as in, “Come to think of it, I do want those 1x2 plates separate from the 1x3s because I use them more often.”

If this is the case for you, please skip to Section III: Constraints.

Hmm, I wonder what I’ll do with these? Photo by author.

C. You’ve been building sets and you’ve developed a clear sense of what you like to build most. For example, “I love to build castles,” or “Technic cars are the way!” You might even have also already decided what you want to do with your builds once completed, such as, “I’m just going to display these in my living room so the other people in my life and I can enjoy them,” or “I have an Instagram account or YouTube channel which focuses on how I did my latest build,” or perhaps you want to engage in other forms of displaying your work publicly.

In these instances, you’re probably already developing a collection of pieces that specifically facilitates whatever it is you like to build, and you may already have the beginnings of an organizational plan, as in, “I keep all my castle-building parts separate from other things, but I want to organize them more.” In general outline, the latter is an approach that some seasoned collectors use as a way to easily get to pieces needed for a particular type of project as a subgroup of parts within a larger collection. If you’re at the point of knowing what you want to focus on, please skip to Section III: Constraints.

Of course, each of these routes into having a bunch of LEGO pieces are not exclusive of one another. There are many people who like a particular set and want to be able to rebuild or modify it in “just the right way” while also being partial to random pieces that they can assemble into new creations—and concurrently being a parent or other caregiver who has inherited a child’s unorganized collection of pieces and figures from a variety of sets or from purchases of individual pieces. The way you go about organizing the pile can reflect a myriad of goals and thoughts about LEGO or reflect just a few, up to and including, “This is such a mess! I just want some LEGO-free space!”

At its most basic, your LEGO organizational system should be one that helps you remember where you put the things you most want to be able to get ahold of. At its best, an organizing system can help facilitate your further development in this area.

LEGO pieces: ready, willing and able. Photo by E. Triffleman.

As we mentioned in the Introduction, and regardless of your route into having a bunch of LEGO elements, you should read Tom Alphin’s excellent, comprehensive and free organizational guide for detailed advice including some of the strategies we talk about for adults in this series of articles. In the guide, Alphin quotes the very funny and unfortunately accurate piece from 2001 by Remy Evard, “The Evolution of LEGO Sorting,” in which (SPOILER ALERT) an adult starts and then ends with a large, unsorted pile of LEGO pieces with stops along the way for organized and hyper-organized strategies, followed by becoming overwhelmed and resigned.

Alphin’s explicit purpose in creating his guide is to help people avoid the latter two states of mind, a goal we share. It’s important that you pick strategies that are actually workable for you rather than ones that might theoretically seem the best but which don’t really fit your current circumstances or mindset.

Tom Alphin’s LEGO Storage guide

In his guide, Alphin reports the results of an informal survey of nearly 200 individuals and discussions with others from a variety of LEGO-related venues that indicated that most adults beyond a certain age tend to engage in systematic organizing rather than just having random piles. Similarly, those with collections of around 25,000 pieces or more (whom we believe probably have a 95% overlap with those who are at or above 18 years old) tend to be systematic in their organizing approaches.

Based on his data, Alphin reports three predominant styles of systematic sorting and organizing; by specific part type alone, whether broadly or narrowly construed; by part type first followed by color of the part; and to a lesser extent organizing by very broad category (e.g. bricks, plates, other). Alphin reports that beyond a certain point, relatively few adults and/or those with large collections do little-to-no organizing.

Despite this, we think that there may be real positive, salutary and/or affirming value in purposefully having a portion - whether tiny, small or more - of your holdings in an unsorted state, above and beyond, “Gee, I just don’t have time or desire to sort today, this week, etc.” There is a certain pleasure in rooting around a container of mixed LEGO parts without knowing what you might find there that for some people emulates the enjoyment of playing with LEGO as a child.

Also, sometimes random, interestingly-shaped or interestingly-colored pieces or minifig parts can be the stimuli for a new build or project, especially for people who are having a creative block (pun intended), or who just aren’t sure yet what they want to build. But even for the most die-hard focused LEGO builder, sometimes it’s important to put the “play” back into the “play well” origin of LEGO. At the opposite extreme, if you’re not concerned about finding “that one right piece right this minute” for your build, then not-sorting or not-organizing is less time-consuming than organizing in the short run.

Unsorted LEGO pieces to have fun with. Photo by E. Triffleman, July 2022.

That said, assuming you want to be systematic in how you organize most of your collection, what follows next is a section about the real-world constraints in which acquiring and organizing LEGO occurs. This is followed subsequently by Section IV: Organizing Strategies and Styles which has a few different examples of how people sometimes use LEGO and organizing strategies that potentially match those uses.

III. Constraints: Budgetary, Space, Time and Temperament

Photo taken by author at LEGO Brand Retail Store, Beachwood, OH.

First and foremost, before thinking about what the “best” way to organize LEGO is, it’s important to be realistic with yourself and your situation. The first has to do with money. Even if you get most of your LEGO pieces from yard sales, thrift stores, or your neighbors down the street, buying or otherwise acquiring LEGO can quickly become a habit. Buying the items that keep all the pieces separated or together – even if they’re as humble as baggies or paper cups - also accrues costs over time.

Going to IKEA or Target and buying a set of shelves or drawers? Even if you solely buy online, the shelves or drawers cost something, even when you build them yourself. And if you get ambitious and buy “real” furniture for storing LEGO (as at least one of our ILUGNY members has done), that’s definitely going to cost you in terms of buying and moving the furniture. How much do you want to spend? How much are you willing or able to spend? These are important questions for each person to consider.

Another aspect of being realistic has to do with space constraints. Whatever types of containers, drawers, shelves, cups or baggies that you use to maintain your collection, they are going to take up space. As Bill Murphy, an ILUGNY member, put it, “LEGO [and the containers they are put into] are like a gas: they will fill all of the space you give them.”

Photo by D. Griffith of his space-efficient LEGO storage area.

For this reason alone, you could wind up deciding that what’s realistic for you at the present time is what Tom Alphin suggests in a different context: sort into a few very large categories, such as keeping all the bricks together, all the plates together, and then everything else together. You can then put them into three large bags or boxes that can then be stowed under the bed or the couch or in a storage ottoman. It’s still more organized than a random pile and you won’t trip on them as much. The trade-off is it will cost you in the time you put into finding the individual part you want out of the whole bag.

After you’ve considered the money and the space issues, a final constraint to be realistic about is the time you have to put into sorting and organizing, what your level of motivation is, and what type of temperament you have. The physical act of sorting parts and pieces is time-consuming (and we’ll cover an idea or two for speeding up sorting in Part 2 of this series), so being clear with yourself regarding how invested you are in keeping things tidy and the extent of that tidiness is important to do.

Ask yourself, what will drive you crazier: not being able to find that one excellent part or minifig torso at the moment you want it? Or will you be driven mad by spending the time to find that one excellent part from all the other parts that are sort of like it but not quite or that are a slightly different color or size, etc.? For some folks, a little bit of looser organization might better fit the number of hours they have available in creating and then maintaining their system of organizing. In fact, sometimes looser organization might not incur more time spent looking for a part because a particular individual might use closely-related parts interchangeably, perhaps because the distinctions between parts are not enough to warrant separating them or because you have only a few of certain similar parts.

In contrast, for other people, a looser system of organization would seem chaotic and time-wasting. Our collective advice is: you know yourself and you know how much time you have to spend on not just initiating but also maintaining your organizational system. Organize your LEGO elements to the extent that makes sense for your purposes.

A little bit of looser organization in progress: curves and rounds. Types are together but partially sorted by color. Photo by author.

IV. Organizing Strategies and Styles

So once you’ve gotten clear about your goals (if any) for LEGO, your constraints, and your relative need for order (or lack thereof), what follows are some specific use cases concerning LEGO pieces for 3- and 4-dimensional builds and some suggestions regarding how you could think about organizing them. (We define 4-dimensional builds as ones with motors and/or that actively change position.) Strategies for organizing parts for baseplates and/or large plates, and for materials for two-dimensional mosaics are considered in Section V: Baseplates; Mosaics of this article. Organizing, storing and displaying minifigs will be handled in Part 3 of this series of articles.

The strategies that follow are not comprehensive – there are probably as many ways to sort LEGO as there are types of pieces. In giving examples of strategies matched to uses for LEGO elements, we also don’t want to suggest that using a different organizing strategy than the ones we suggest would be “wrong.” What is best for you and your builds is what works for you.

Sometimes you just wanna put something together for the fun of building. Photo and build by author.

Use Case 1: Engineering without concerns about conventional visual appeal

Is your goal at the moment to just build a 3- or 4-dimensional project with a high priority on structural stability, have some fun, and not pay attention to conventional visual presentation? (For examples of typical visual presentations, see BrickLink’s MOCs gallery.) Then it might make good sense to organize on the basis of part type and potentially subtype followed by size without bothering with sorting by color, at least in the initial stages.

In this example, all the round plates in a collection would be in a large container, sorted into 1x1s, 2x2s, etc. The 1x1s with an opening in the top might or might not be separate from the 1x1s without an opening, depending on whether you actually use them for different purposes. But whether they’re blue, green or purple might not matter for a particular project in this instance as long as the parts and the build hold together well. So the parts are not sorted by color.

A structurally stable moonbase with a unified color scheme; build and photo by B. Wygand.

An equally stable build and photo by B. Gaudreault.

Use Case 2: Engineering with Aesthetics

This is the situation in which you want to build a highly stable, finely tuned project that also looks visually appealing at the end. This probably characterizes a majority of adults with LEGO collections who also build. In this instance, you may be better off sorting first by part type and subtype, followed by size, and then by color. In this example, all the plates with grips or holders are put in the same general area or container, but those with vertical grips are held in a separate section from the plates with horizontal snaps (see picture below).

Screenshot of plates with grips and snaps from LEGO.com Pick-a-Brick webpages, accessed 01-25-2023.

In further organizing these parts, 1x2s are then separated from 1x1s. Then, all the sand green 1x2 plates with vertical grips are kept separate from the dark grey 1x2s with vertical grips.

Use Case 3: Artistic Endeavor facilitated by Engineering

Is your goal to build something that is more artistically- or visual-design-driven, with the engineering as an important but not primary driving concern? In this case, you may do well with two approaches among the many that exist. The first approach is the same as Use Case 2 above as the engineer who wants their build to stay upright while looking good: organize by part types and subtypes first, then size, then by color.

But when visual appeal is the primary goal, another way would be to organize parts first by color and then within each color to organize by part type and size. In this case, all the different types of sand green parts are co-located, but within that space, each type of plate is separated from one another and also organized by size. This could be considered the “Rainbow Way” of organizing LEGO because the end result can show all the red parts are kept together, all the orange parts together, etc. As we understand it, this is how some LEGO designers and Master Builders organize portions of their workspaces, in part (no pun intended) because it looks nice and it also makes it easy to find at a glance where that bunch of bright orange small slopes has wandered off to.

A Master Builder’s Rainbow. Photo by M. Graham.

Use Case 4: Selling Parts

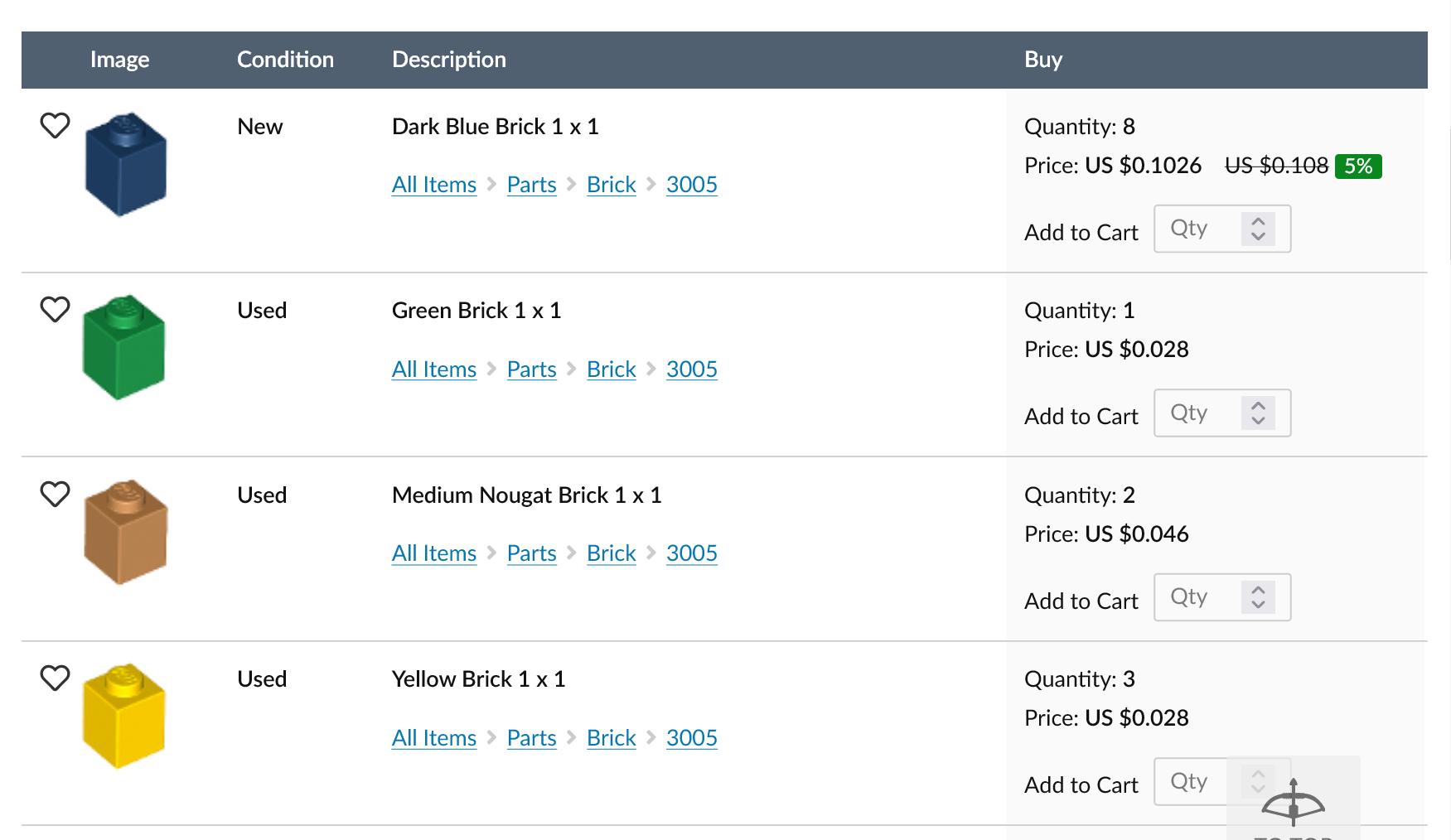

While some people who sell LEGO parts also build, some do not. If you’re in the latter category and you’re selling parts mostly or solely online, we suggest you use an organization strategy based on whatever platform you’re selling on. For example, BrickLink uses a system similar to but not identical to that of LEGO’s website. With the exception of the LEGO website, the vast majority of platforms that sell LEGO elements do so on the basis first and foremost of new vs. used pieces, an important distinction in the realm of LEGO pieces. (LEGO.com only sells new parts.) Considering these factors, you may want to store new pieces in separate containers from used pieces.

After this difference, parts are sold on the basis of types of pieces and subtypes, size, and then colors. On eBay, items are indexed by the listing’s title words. Additionally, in order to be congruent with various search filters, there are also characterizations which include whether the part is new or used; type of part (brick, window, etc. but interestingly, not plate as of this writing); how many items in the lot; type of set from which the part came and a variety of other parameters.

Screenshot of Bricklink listing, accessed 01/01/2023, Store: Elementary.

Use Case 5: The Mixed Approach

Having discussed these use cases, it is also true that regardless of the kinds of building or selling that you do, a mixed approach can also work as long as such a system works for you and you can keep track of it. An example of a mixed approach would be: A) some pieces which fit an overarching content theme or decorative category are kept together while B) other unrelated pieces are separated on the basis of type, size, color, function, etc. as needed.

As an example of putting content areas together, all the plant-and-flower-related pieces can be kept together in one segmented container, and then further separated within that container on the basis of various criteria such that all the tree branches are together in the same container separated from grass and flowers, but the small lilac branches are separate from the large dark green branches. They all belong to the same theme and serve a similar function, but the visual impact of each sub-grouping is different.

As another example from the same overall collection, SNOT bricks (modified bricks in which the Studs are Not On Top) can be kept separate from the standard-style System bricks since SNOTs serve a different albeit related function to bricks. The SNOTs can be separated by the number of knobs and then colors, while the bricks are separated first by color, then by size.

The advantage of this mix-and-match approach is that it is more likely that grass and trees might be used for similar purposes in a build but would likely be used very differently than bricks and SNOTs. Some Master Builders also use a mix-and-match approach to organizing, but based on an initial dichotomy of frequently used parts vs infrequently used parts. The frequently used parts might be sorted by color first, then by part type; while the infrequently used parts might be separated by part type first, followed by a variety of other criteria.

Floral and plant pieces residing in different containers than shades of purple bricks and plates. Photo by author.

Still another mixed approach is that of a “collection within a collection.” As we mentioned earlier in this article, many LEGO builders have a particular interest in one or another specific type of build, such as castles, moonbases and so on. In turn, many of these builds have “standards,” or methods and specifications by which to build sections of a larger whole that all connect to each other (for example, so that one part of a moonbase will connect easily with and look consistent to the next section), most often in a collaborative context. (For an example of a standard, please see TwinLUG’s Micropolis Standard.)

This means that there are specific parts that are required and necessary for such builds. These builders therefore keep the parts for their standardized builds separate from the rest of their collection, using whatever organizing strategy is useful for them within that segment of their collection while potentially using a different strategy for the remainder of their LEGO pieces.

Examples of an organization system for larger collections. Photo by B. Gaudreault.

There are also approaches that are deeply detailed and nested, which work well for large and very large collections. As an example of such an approach, ILUGNY member Brian Gaudreault sorts first on the basis of connector type, then by design type or subtype, followed by whether the part does or does not have a certain feature, such as hinges or knobs.

For example, one category is “LEGO knob/stud bricks”, which he divides into multiple containers such as “LEGO knob/stud bricks basic 1x1-1x3”, “LEGO knob/stud bricks basic 1x4-1x16”, “LEGO knob/stud bricks basic 2x2+ (& 2x2 corner)”, and so on. Brian then determines whether a given part should be placed into containers for specialty pieces, instead of into containers for “basic” pieces.

After that, he decides whether to further separate parts on the basis of color. This works well for Brian because it also allows him to keep track of his inventory more easily, an important factor in dealing with all collections, but especially in dealing with large collections. Keeping track of everything you’ve accumulated, whether organized or not, is an important part of the whole and will be addressed in Part 2 of this series.

V. Baseplates and Large Plates; Mosaics

LEGO Baseplates, large and small.

Those working in 3-and 4-dimensional LEGO structures and those working on more 2D (aka flat or mostly flat) creations such as mosaics should also consider whether or not the baseplates (or other items that one attaches LEGO pieces to, such as large plates) need a specific organizational plan. Unlike the vast array of LEGO pieces and/or minifigure components, there are a relatively limited number of types and colors of LEGO-manufactured baseplates (in contrast to the larger universe of plates), which form the most basic foundations on which LEGO structures are built.

Some people go a step further and alter baseplates to create custom building surfaces, in which case knowing where and how those are stored is also useful. There are also the components that LEGO sells as part of its “Art” product line which can include not only simple baseplates but also multi-baseplate surfaces with various systems of brick-built reinforcements designed to accommodate the weight of mosaics, to provide framing, and to provide a way to hang the final piece on a wall.

Like all other LEGO products, the need for an organizational plan for baseplates and large plates should probably be driven by how many of these products one has. If you only have three or four baseplates, then it’s sufficient to just keep them in a safe place without direct exposure to light, stored horizontally and without weight on them to avoid warping, without further organizational efforts. Beyond this limited number, though, some form of organizational system is useful. For baseplates or large plate pieces, organizing by size (16x16, 32x32, etc.) and by color might be sufficient.

But if you are also keeping track of the components used in the more elaborate multi-plate and/or brick-built surfaces used for mosaics, you could organize first by function and/or by type, then by size and color or vice-versa. For example, the pieces for hanging mosaics (3x5 panel with 4.85 hole, element 67139 on LEGO.com) and the bricks used for reinforcing baseplates could be kept in the same segmented container – the common function being things that are important for securing the surfaces to which one attaches LEGO elements to – or they could be kept separate from each other, with the 16x16 black bricks kept together but separately from the 2x16 white bricks which are also used for the frame or reinforcements.

Some of the parts used for creating the surface on which to attach mosaic pieces. From LEGO.com’s Pick-a-Brick for set 31203 World Map, accessed on 01/25/2023.

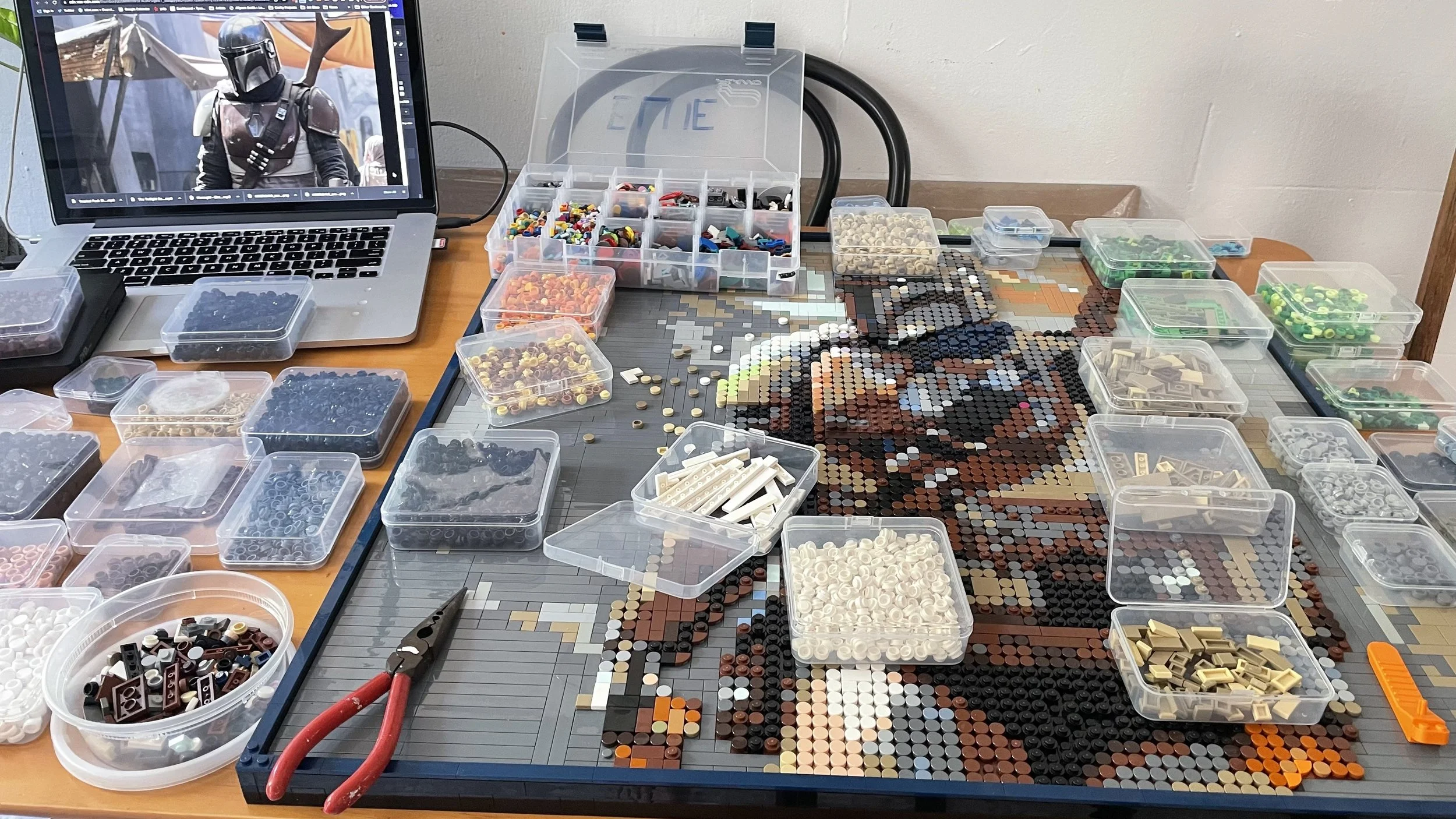

In addition, for people who build mosaics, there is another issue to grapple with when thinking about how to organize: what kind of mosaic are you building? Are you creating something that is two-dimensional, such as something made solely with 1x1 round tiles or with only one type of plate (excluding the baseplate and framing)? If so, then your organizational plan probably could easily be: keep the colors separate from each other in whatever color-based or monochrome groupings make the most sense to you; the end.

Mosaic building in progress by Tyson S.; photo by Tyson S.

But if you’re also working with other types of pieces, then you’re in a similar – though not identical – organizational realm as those who build more overtly three-dimensional objects. If this is the case, your organizational plan might be every bit as detailed as the person who is building dynamically engineered structures that also look good (Use Case 2 in Section IV), who organizes by type first, followed by subtype, then size, then color.

While you might wind up with the same kinds of pieces as the aesthetically-oriented engineer, the mosaic builder could use them for the purpose of building visual or textural variability within a given mosaic. To the extent that this is the case, you could organize your pieces along the lines of what role the pieces are playing in your work: “things that add depth” or “circular pieces” could become categories with pieces then separated according to height or other size-, shape- or texture-related criteria in addition to color.

This is one way in which mosaics are different by degree from three-dimensional builds: generally speaking, apart from the baseplate or large plate and the frame, there are probably not going to be as many (or even any!) structurally important parts that are not also visually evident to the viewer. Therefore, one’s organizational plan could put a priority on visual and tactile characteristics.

Mosaics with varying textures and pieces.

Mosaics and photos by Tyson S.

VI. Conclusion

As we’ve made clear in this article, how you organize your LEGO collection is in part all about how best you’ll remember to find things when you want them. In the next part of this series, we’ll discuss the physical and practical aspects of organizing LEGO, such as recommendations about the containers, drawers and shelving one can use; labeling containers, drawers, etc.; and how to maintain an inventory.

What is your organizational strategy for managing your LEGO parts collection? Let us know in the comments below.

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Charlie Stephens, Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, Andy Price, John A. and Lukas Kurth from StoneWars to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.