Giving a Clue: Offering Feedback to New LEGO Builders

/Constructive criticism within the LEGO community can be hard to give and take, especially between two people of vastly different skill levels. I’d like to share some thoughts that I used recently when my soon-to-be TFOL and I collaborated on a project for a LUG display. He’s a decent builder for his age but has difficulties with the revision processes. I was not at all sure how it would go—we have similar personalities and interests, which can lead to a good time or a lot of head-butting.

“Let’s Play a Game” Display, Featuring CLUE, Warhamer 40K, D&D, Chess, Settlers for catan, jenga, and Mobile Frame Zero. Thanks to Parker G and Chris H for the Mimic and Jenga respectively.

Overall, things turned out very well, but unfortunately, I only have pictures of the finished product. My family enjoys playing board games, and I decided to do a board game-themed table at my LUG’s big annual Christmas display. I wanted a mix of classic, well-known games and some that not everyone would necessarily know, as well as builds that represented the games and some inspired by the game. For one of the classic games, I chose Clue (Cluedo). My son was super excited about Clue, and we had just let him watch the movie recently—he had lots of ideas.

Keep It Manageable

In the AFOL community, when we hear “collaboration” big things like New Hashima come to mind. Collaborations can be small, too, and are a great way to teach! Small sections can make a project feel more manageable to less experienced builders. Clue is easily broken down into nine rooms, six characters, and six weapons. The game's story can be easily told through small vignettes instead of building a replica of the game board.

The Minifigure Habitat standard is great for vignette building and is designed to link together, which gives the individual habitats a linked feel to match the Clue mansion! Six of the nine rooms work really well in the small 8x8 habitat footprint, (the Lounge, Study, Conservatory, Kitchen, Billiards Room, and Library). The Dining Room and Ballroom would be very difficult to convey at a small scale so were built as 16x16 habitats. The Hall could have gone either way but was added to the larger format rooms.

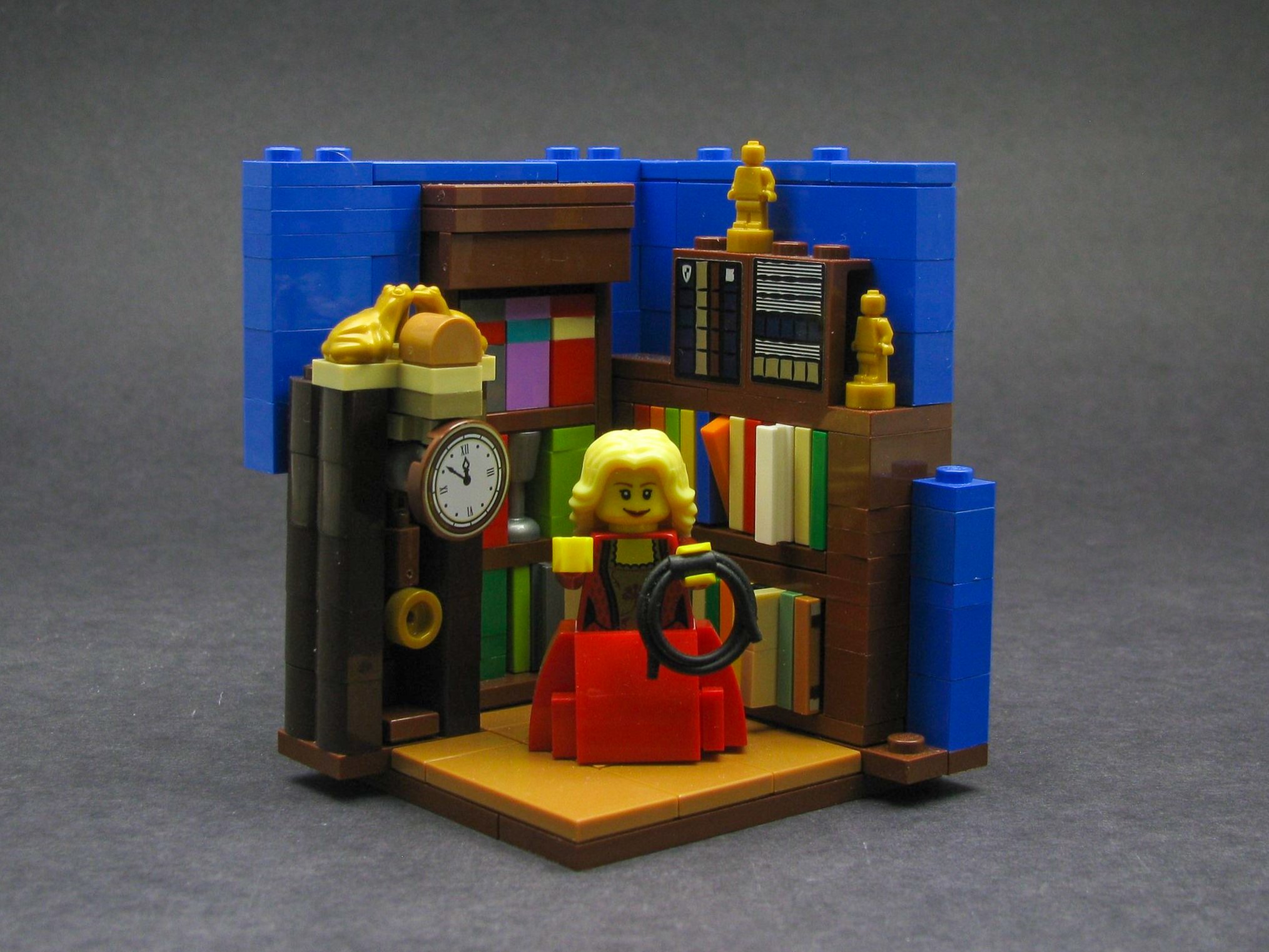

Mrs. White in the Hall with the wrench

The plan was for my son to build the Library and Lounge and help with some of the bigger rooms. He decided to surprise me and also tackle the dining room on his own. The small size of the rooms helped keep things manageable as far as expectations, build time, and available parts. Plus, reworking a small area of a hundred or so pieces is a lot less daunting than reworking thousands of pieces that can quickly fill even an area of a 32x32 baseplate.

Always Find Something Positive

There is a difference between “Hey, look at this thing I built!” and “Help me make this better!” The first is mostly looking for acknowledgment but not suggestions; the latter is looking for details for improvement. When a child or a less experienced AFOL shows you something and is looking for feedback, it can be hard to not just see all the areas in which you would have made different choices. Even if it’s small, find something you like to lead with, even if you feel it may be basic. “This is a nice color choice,” or “The minifigure posing is so dynamic,” or “Good SNOT use,” etc.!

The library, with Miss Scarlet and the Rope ,went through a lot of iterations but in the end my son was super pleased with it

Keep Critiques Small and Manageable

Do not drop a ton of critiques all at once. Let’s say the build has very few interlocked parts and is fragile, and there are a lot of details that could be improved. Start with the big structural issue first. Find out why it’s not interlocked. They might have made that choice because they don’t have any 1x1s or 1x3s in that color. How might we help with that?

A classy Billiards room, man a pool table is hard to fit in an 8x8 space!

You could walk them through a series of questions. Will a different color work? Could we use 1x2s that overhang in the back that we won’t see from the front? These questions teach how to think around parts limitations. My suggestion from personal experience is to make it a conversation, not a demand. Once the big issues are solved, get more detailed. Always keep in mind the above style—ask questions and lead them in the collaboration gently.

Don’t Take Over

It is very easy to take over—resist this urge at all costs! If you take it over and do all the work, they will likely get bored and quit. If the solution is complicated, you can talk them through it step by step, i.e. “this goes here, that goes there. Or you can do a buddy build. Gather all the pieces you need for two copies. You build one step at a time, and they then mimic you like a living LEGO instruction book or learning a build from a video!

MR. Body dead in the Ball Room

Speaking of instructions, if you can find a set of well-made instructions (by LEGO or someone else) that solve a similar problem, you can use those as a reference. “Hey, use these instructions to start, but we need it bigger/smaller/wider/more blue. See what you can do, and then we can talk some more.” This worked really well with my son on the Library bookshelves. I handed him the instructions from the Modular Bookshop set with several styles of bookshelves earmarked and said, “Start with one of these and then maybe show me what you come up with to make them your own.”

Iterate, Iterate, Iterate

You’ve likely picked up that this is an iterative process already, but make that clear to the newer builder you’re mentoring too. This is going to take a few tries; we’ll learn a lot, but we may have to rebuild a few times in the process. Emphasize the need for each part of the collaboration to support all the other parts. Finding things to compliment gets easier with the iteration processes, too, as you can focus on the growth between revisions.

Mr Green in the Kitchen with the Candle Stick

Give Them Space But Check In Occasionally

You don’t have to check in every iteration, but ever so often should be good, especially with kids or teens. “Are you having fun?” or “Have you solved any problems?” and similar questions are good to ask to start the conversation. This was vital to our processes. It let me know if the amount of feedback was right for my son and if he felt the process was still worthwhile.

Professor Plum in the Conservatory with the Knife

Building LEGO should be fun! Yeah, there is always a point in a big project where it gets to be a slog, but especially when coaching younger builders, sucking the fun out of building is the worst thing you can do. Avoid the temptation of perfectionism to let them express themselves in their own way through the bricks.

Be Willing To Fall Down Rabbit Holes

My son really wanted his dining room to have a stained-glass window. So we went down the rabbit hole of using old-style fences, turntable bases, transparent cheese slopes, and more. This helped to keep it fun and encouraged him to learn new techniques. The ability to explore skills in a self-guided way keeps the “this is work” feeling at bay. But one word of caution—allowing for this takes planning and time, so be careful of falling down too many rabbit holes when there is a deadline!

Colonel Mustard in the Dinning Room with the Revolver. With the stained glass Rabbit hole. (I’m not sure why we needed a gold Harry Potter Statue but compromise is the nature of collaboration.)

Be Vulnerable

Get feedback from the person you are helping on your part of the build. My son never had any specific critiques other than what he liked, but that’s ok. Asking for feedback on your part emphasizes that you are listening to them and that we all have room to grow. I’ve learned that sometimes the “dumb question” that no one is willing to ask but everyone is thinking can be the key to solving a problem.

A very nautical Study

The question or comment of someone less experienced can lead to removing assumptions we’ve forgotten about and lead to more creativity. Also, as a benefit, you are teaching them how to teach so they can, in turn, pass their skills along someday!

Encourage Growth Measurement

It is so very hard to not compare ourselves to others. When guiding less experienced builders, it is important to focus on their growth. It is pretty much guaranteed there will always be someone who has more bricks, more building time, more experience, more, more, more. By setting perfection as a benchmark, we set ourselves up for failure every time.

MRS Peacock in the Lounge with the Pipe. The fireplace took a few tries to get to this design. lots of questions and rebuilding.

As a welcome alternative, take pictures of the first build (I wish I had and not just for this article!) and subsequent iterations so you can see the growth. Look back to older MOCs and point out the skills that have developed. If possible, show your old MOCs and talk about what you’ve learned since then. (Though don’t focus on the growth of the available parts pallet, we can’t control that.). Acknowledge failure if it happens—sometimes things just don’t work out—but be sure to make a connection and try something new. The goal is growth, not perfection.

Putting It All Together

When we finished the build, I asked my son what he thought of the processes. He said, “It was fun, I liked learning new techniques, and I would do it again.” Now that is some successful coaching!

the full clue mansion

This article actually ended up a bit longer than I thought it would be! Not everything here may work for everyone, so take what works in your situation. Different people who are exploring LEGO may need different amounts of guidance depending on age, skill level, personality, and so on. Ultimately, the key is to not overwhelm your budding builder—if you keep it enjoyable, you are sure to build good memories together.

Have you helped another builder to learn a technique? What other tips would you suggest? Let us know in the comments below.

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Charlie Stephens, Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, Andy Price, Lukas Kurth from StoneWars, Wayne Tyler, Monica Innis, Dan Church, and Roxanne Baxter to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.