Confessions of an Anti-Digital Builder

/Once upon a time, I was a real-bricks-only builder. And—I was biased. Not only did I personally prefer physical bricks, but it seemed to me that digital building was basically cheating. Too easy, too fake. Not in the true spirit of LEGO. Like putting wax on fruit to make it shiny. In one word, insincere. (Fun fact: sin cere… is Latin for “without wax.” Okay, so it comes from jewelry, not fruit… but still.)

I doubt I would ever have put it quite so straightforwardly back then. I just kind of thought, “Aw, here’s a build that would have been good, ruined! It’s all digital and there’s nothing really there!”

I even remember with burning distinctness a comment I made on a digital build, after saying that it was too bad it wasn’t real bricks. “I don’t know, I just have that, ‘Why digital?’ mentality. :P ” I was conscious of my bias, even back then—we’re talking 8-10 years ago—but I didn’t have any articulate reasons for it.

Contrast that mindset to now. Last year I spent thirteen weeks doing intensive digital building. I think I had already lost some of my unreasonable bias, but those thirteen weeks completely changed my perspective. Digital building is definitely not too easy. It’s at least as real as a dismantled MOC that lives only in pictures. And I’m going to argue that digital building is well within the spirit of LEGO.

Is Digital Too Easy?

Building with LEGO as an art form is all about the limitations. There’s only so much you can do with hard plastic already shaped into distinct bricks. Many of the limitations are the same in digital and physical building, but there’s a case to be made for physical building having some limitations that digital building leaps right over.

When you’re building with real bricks, you usually have strict quantity limitations. Even if your collection is huge, you have some quantity limit. You’re even more limited by colors. Mixel joints, for example, are one of the biggest offenders when it comes to colors!

They only work in Grey… Also find the plate pretending to be a MIxel joint.

And then, the laws of physics impose quite a few limitations. You have to consider the weight of your model. For smaller models, builders do this without thinking about it—but there are almost always structural elements that you could have skipped if you were building in a world without gravity.

digital builds never have a rough time making it to the photography session

If you build physically, in order to present your creations in digital pictures, photography also imposes limitations—or at least challenges. Photography is an art unto itself, and skill with the brick doesn’t give you skill with a camera. Especially if you’re building on a deadline, getting the right photography conditions can be a real challenge.

These are all challenges of building with physical bricks that are obviously not challenges for digital builders. Not only that, but digital building has other clear advantages. You can copy and paste repetitive sections. You can undo and redo brick placements to easily see which variation looks better. Sometimes getting that kind of visual can be a real pain in a physical build, if you’re working with a delicate bit. To top it all off, with one click of the mouse, digital builders can change the colors of entire segments of a MOC, allowing them to instantly compare every color combination they can think of.

So after all that, can there really be two opinions? Physical building is clearly far more challenging than digital building. And since LEGO building is all about the challenges…

Is Physical Easier?

But before we jump to conclusions, let’s take a look at the other side. The challenges of building digitally may not be the same as the physical builder’s challenges, but there are definitely challenges.

First of all, minifigure placement is a digital challenge. Things that would take seconds in a physical build take a digital builder painful minutes. Something as simple as having a variety of minifigures posed with their hands going different ways becomes a nightmare digitally. These kinds of slight variations in poses happen effortlessly in physical bricks, but they make all the difference in the world to a natural minifigure pose.

Another nightmare for a digital build is loose techniques. Any kind of scattered technique—water, grass—essentially any part of a creation that’s not firmly connected with a connection point the digital software recognizes—is a slow drag for a digital builder. Some physical builders will appreciate this point more than others. If you’re the kind of builder who starts to hold your breath whenever someone else gets near your MOC, then you know how much more you can do with bricks if you’re not worried about connecting them!

Texture is also a digital challenge. Copy and paste is a useful tool, but it can be tempting to overuse it—and then you end up with repetitive textures that look unnatural. In a physical build, nothing’s easier than introducing a slight variation as you build repetitive sections of landscape or wall. At best, achieving the same level of detail in a digital build nullifies the benefits of the copy and paste function. And there are textures that are extra difficult to achieve—vegetation, for instance. No one worries in a physical build about having all the grass stems sloping in exactly the same direction—the variation is too great. In a digital build, it takes a lot of extra time to rotate stems to make it look organic!

While it may seem like there are no quantity limitations for a digital builder, in reality, rendering huge MOCs takes a long time—and in fact, once you’ve got past a certain amount of bricks in your creation, the digital software starts to slow down. There are limits!

What about photography? Although a digital builder can skip the camera, it still takes a special skill set to get a good render with the right angle and a realistic pose. I think there’s a slight misconception here, as physical builders frequently seem to think that digital builders have an easy time presenting their creations well. Rather, what happens is that people who are attracted to digital building tend to already have computer savvy skills and either know or quickly learn how to render well and post-process for a photo-real presentation—whereas good physical builders don’t necessarily have any aptitude for cameras or photo-editing.

There’s another limitation to digital building that it’s easy for a physical builder to overlook. Rummaging around in a part bin, inspiration is often easy to come by as you spot an unusual part. Although digital builders have the whole LEGO selection at their fingertips, it’s not nearly as simple to just “stumble on” the right part. Sure, you can scroll through a Bricklink category, but visualizing parts you’re not familiar with isn’t so easy and for the most part, I found that I had to think of what I needed before I used it.

Weighing the challenges, I’m not convinced that the physical builder has the harder job. Of course, which one you personally find easier will depend on a lot of other circumstances—but maybe it’s time to let go of the feeling of unfairness when digital builders take advantage of their ability to use colors that don’t exist, or gravity-defying techniques. Physical builders don’t scruple to scatter loose bricks around when it makes their creation look better!

Is Digital Too Fake?

Beyond the difference in the challenges presented by digital or physical building, there’s also of course the difference in the final product. A physical build is real. You can touch it, put it on a table, admire it.

Obviously, this is a legitimate difference when it comes to, well, physical builds. For a display shelf at home, or a display in a mall, or a display at a LEGO convention, physical bricks matter! But sometimes—maybe the feeling is unique to me, but I’m guessing it’s not—the satisfaction you get from seeing a physical MOC in real life is still present to a lesser degree when you see a physical MOC in pictures. On the other hand, that feeling disappears when you’re looking at a render. For me, this translated into a disappointing feeling of, “There’s nothing really there. It’s fake.”

If you take a common-sense look at it, that reaction doesn’t make much sense. Why should a digital MOC—probably with the original files still saved and retrievable—feel less real to you as a viewer on a digital device than a physical MOC that has long since been broken down into its component parts?

For me, overcoming the “digital is fake” bias was a combination of a greater appreciation of the challenges of digital building plus a realization that it just doesn’t make sense to categorize digital MOCs as fake and physical MOCs that have no life except in digital pictures as “real.”

Of course, digital builds and physical builds will always have different flavors—one associates itself with little pieces of hard plastic while the other associates itself with a mouse. But the important thing—and my point here—is overcoming the unreasonable prejudice that leads some of us to use “real” as equivalent to physical… and by implication, if not explicitly, calling digital MOCs “fake.”

Is Digital Too Cheap?

Let’s face it, LEGO is an expensive hobby. These plastic bricks can swallow thousands of dollars a year. That’s not something everyone can afford, even in first-world countries. But a laptop (which most of us have anyway) and free digital building software? That’s far more accessible financially. There’s no question that digital building levels the playing field and gives more LEGO fans a chance to see their ideas come to life in bricks.

So… what does this have to do with the anti-digital bias? Well, think about it: you’ve spent more than you’d like to think about on that massive collection gathering dust in your basement, haven’t you? How fair is it that some kid who hasn’t spent or invested a penny on a single real LEGO brick gets to swoop in and score a win and maybe prizes in a contest from LEGO Ideas?

I make this point with some hesitation. The LEGO community is incredibly welcoming and open, but I think just a smidgen of this feeling is sometimes hiding deep down where we don’t recognize it. In fairness to myself, I don’t believe this entered into my bias; my LEGO spending has always run on a shoestring budget and I fully appreciate how expensive the hobby is. (That’s not in itself a safeguard; it would be easy for me to feel like I’ve sacrificed to build up my physical collection and digital builders haven’t. But I always knew it was my own choice to build physically rather than digitally.)

Still I think—I’m not sure—but I think I might have seen the feeling crop up once or twice in unexpected places. And I suggest that looking at digital building as “cheap” is looking at it in the wrong spirit. Instead, we should embrace this opportunity to level the playing field and let everyone participate.

(Note: I’m certainly not arguing for digital building being allowed in every competition—it’s as legitimate for there to be physical-only competitions as for there to be castle-only competitions depending on circumstance. What I’m saying is that, when it is allowed, physical builders need to be careful to appreciate the opening of the field to more players and more creativity, instead of feeling like they’re being cheated.)

The Spirit of LEGO

At the beginning of this article, I said I was going to argue that digital building is well within the spirit of LEGO. So first of all, what is this spirit of LEGO?

Of course, LEGO means different things to each of us, and I’m not claiming to have the last word here. But condensing what I’ve seen in my nearly nine years as a MOCer, here’s what I think makes LEGO MOC building unique.

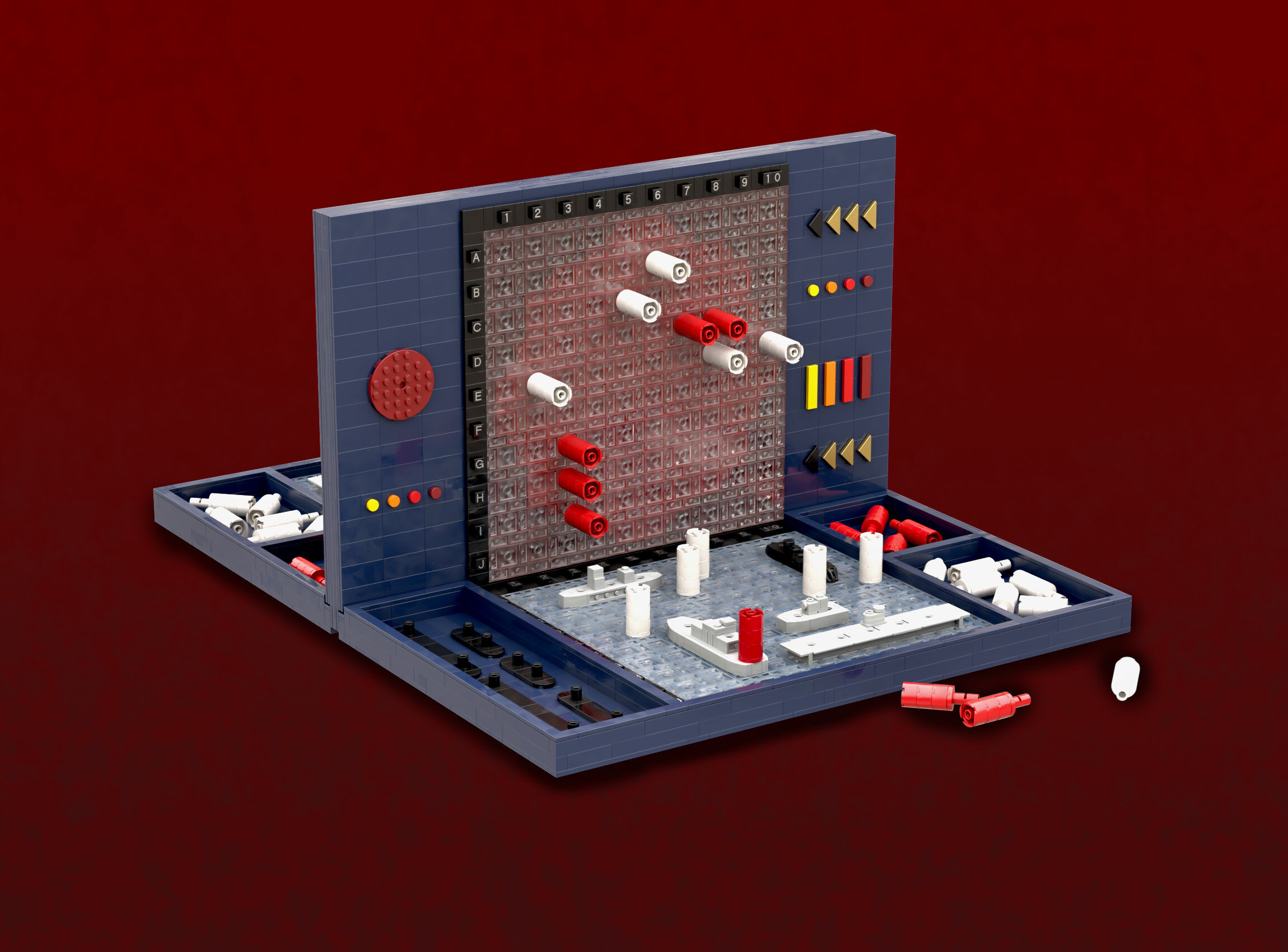

If you pick up a paintbrush, find a canvas, and start ruining it with a hodgepodge of untrained color, who’s going to think that what you paint is any good? Your mother maybe—but unless you are one of our multi-talented readers, no one else. But consider picking up a handful of LEGO bricks and turning them into something like this:

If I had drawn that, not only would it not have looked as good (my drawing skills being what they are), but even if it had—there would have been nothing special about it. But the fact that it’s made out of LEGO means there was an element of problem-solving. Even the simplest creation has had to overcome obstacles in order to be what it is, and that brings value into what, if it were created in a different medium, could very well be rubbish.

Here’s my point in a nutshell: LEGO building is a fascinating intersection between art and problem-solving. Of course, other forms of art often involve problem-solving as well (any author who has faithfully followed Murphy’s Law knows that...), but LEGO building always and inevitably has this element. You start off with prefabricated, predetermined bricks and you try to find a way to make them work together, to transform them into the vision you have in your head. Some LEGO builders focus more on the art, others more on the model building—but we all have a common core of problem-solving that unites us, whether we’re the artsy type or the engineering type.

What does this have to do with the spirit of LEGO? I suggest that it means that the spirit of LEGO is, at its core, a spirit of problem-solving—a spirit of taking tiny, insignificant pieces and turning them into something stunning—a spirit of taking your limitations, dissecting them into their smallest components, and then putting them back together ideally in such a way that the final product will be better, not worse, because of those very limitations. Few MOCs completely embody this spirit, of course, but every time we find the perfect parts use—every time we stumble over the perfect marriage of textures and colors—every time we make the 2 stud to 5 plate SNOT rule work to our advantage—that problem-solving spirit, the urge to take trivial things and turn them into something great, is shining through.

If I’m right about this being the core spirit of LEGO building—if problem-solving is the foundational impulse that we’re all tapping into—then only a misunderstanding of the challenges of digital building could lead us to consider it as not a valid part of the LEGO MOCing hobby. Yes, digital builders don’t get the hands-on “real” experience physical builders do. Yes, they don’t face some of the limitations physical builders face. But at the end of the day, digital builders do just what a physical builder does: take little bricks covered in studs and anti-studs, snap them together, and solve problems one by one in order to bring their artistic vision to life.

Conclusion

My thirteen weeks of digital building didn’t turn me into a digital builder. I got back home and went straight for my physical bricks. I’ve hardly touched Stud.io since. But I do have a new appreciation for the challenges of digital building. If LEGO is really about the art and the problem solving, then maybe a good render doesn’t have to yield to a well-photographed physical MOC.

Digital bricks and physical bricks both have their strengths and weaknesses. Let’s face it, we won’t be seeing a table full of digital builds at a LEGO convention anytime soon. But digital building lets builders who otherwise may not have had the money or the space show us their creativity in bricks. Some of the limitations of digital building are different than the limitations of physical building—but the essential limitation, the need to work within the LEGO system, is still there.

I encourage physical builders to perhaps take a second look at digital builds and recognize that the same valuable problem-solving skills and the same creative effort that goes into physical builds also underlie digital creations. Why should there be a stigma attached to digital builds, a feeling that digital builders have cut corners to make what they made? Whether you work with hard plastic or with computer software, if you started with LEGO bricks then you’ve ended up with a LEGO MOC that deserves to be judged on its own merits and not prejudged based on the medium.

So however you build—brick on!

Best of BrickNerd — Article originally published September 7, 2021.

What’s your perspective on digital building? Is it a worthy form of LEGO MOCing or should it be used only as a tool to plan for physical creations? We’d love to hear your thoughts in the comment section below. And if you’d like to learn a bit about the history of digital building, check out this previous BrickNerd article, Taking Digital Building to New Illustrative Heights.

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Charlie Stephens, Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, Andy Price, Lukas Kurth from StoneWars, Wayne Tyler, Monica Innis, Dan Church, and Roxanne Baxter to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.