LEGO’s Financial History, Part 1: The Ides of March, 2000 to 2001

/Introduction

This is the first part of what I hope will be a series looking at the history of The LEGO Group from 2000 onwards. On a year-by-year basis, I’ll use a mix of newspapers, annual reports, and other media sources to tell the LEGO story as it was being reported at the time.

Today I will focus on the years 2000 and 2001, but before I do, I would like to fast-forward to 2005, when The LEGO Group announced the biggest loss in its history. These upcoming and seismic events nicely set the context for 2000 and 2001—The Ides of March—documenting the years building up to those difficult times.

The Height of Financial Distress

The LEGO Group’s loss booked in the 2004 Annual Report was the largest in its history.

On 2 July 2005, The New York Times reported on The LEGO Group’s devastating financial results stating “competition from abroad, and the computerization of children’s playtime have turned a rich profit into a deep loss.” The Group had suffered a kr.1.9 billion ($320 million) deficit in 2004, almost double the kr.1.1 billion loss booked in 2003 the previous year.

The Group was in the middle of perhaps the most grueling period in its history. A change in CEO, the disposal of Legoland Parks, operational inefficiencies, significant redundancies, a strategic realignment, large debts, and record losses may sound like a plot from Succession, but this was the real world, and the ‘B-word’ was in the air.

It wasn’t just The LEGO Group’s own internal issues causing distress; the physical toy market was under intense pressure and had a bearish outlook. Christopher Byrne, an independent toy analyst stated, "A traditional toy, like a Lego block set, is still popular, it still has its adherents. But it's a niche product rather than a mass product."

Niche indeed.

The Turnaround

The LEGO Group Annual Report, 2005

But behind these poor results, the foundations of the dramatic turnaround were already taking shape. Licensing agreements and trial Brand Stores had been recently launched and would go on to become cornerstones of the company’s future success. In addition, new CEO Jorgen Vig Knudstorp had already actioned the big changes needed before 2005 started, with the disposal of Legoland Parks, a focus on the core business, and delivering operational efficiencies.

A year later, The LEGO Group’s results had quickly rebounded, with turnover increasing 8% and a loss of kr.1.9 billion being flipped into a kr.0.5 billion ($85 million) profit, marking the start of LEGO’s 20-year march towards world domination. Between 2004 and 2022, The LEGO Group nwould increase sales a staggering 13% per year, and in 2022, they would announce a profit of kr.13.8 billion… equivalent to $2 billion.

The LEGO Group Turnover, 1995 to 2022 (Kr. billion)

Source: The LEGO Group Annual Reports

Now that you have the context of where we are heading, let's go back five years to 1 January 2000 and begin the history proper as we gradually build up to the climax of The LEGO Group’s financial distress.

2000 - Loss

Chapter 1

The Sopranos Season 1

On 1 January 2000, the world woke up with a gigantic sigh of relief as the ‘Millennium Bug’ had not caused the apocalypse. The four horsemen could wait patiently in their stable for the Artificial Intelligence panic of the 2020s.

The soundtrack for the year ahead included 'The Real Slim Shady,' 'Oops!... I Did It Again,' Coldplay’s 'Yellow,' and the underrated genius of Elliott Smith and his album, 'Figure 8.'

In TV land, The Sopranos was coming off the back of a sensational first season and single-handedly shaping the ‘quality TV boom’ that followed… all of which you could watch on the new groundbreaking technology, the Digital Video Disc (DVD).

But in Billund, the last thing on the minds of LEGO’s leadership team was whether Big Pussy Bonpensiero would make it through Season 2 unscathed—they were dealing with their own crisis. The LEGO Group recorded a loss of kr.831 million ($100m), which was described as ‘embarrassing and completely unsatisfying’ by CEO Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen and Deputy CEO Poul Plougmann in Berlingske, Denmark’s paper of record.

The LEGO Group Annual Profit / (Loss), Kr.Billion

Source: The LEGO Group Annual Reports

The loss was only the second in the Company’s history, but rather than being a blip in an otherwise steady stream of profits, it was a harbinger of worse to come. Three years before the financial challenges of 2003 to 2004, the Company had already recognised that a focus back towards the core business would be required, with books, clothes, wristwatches, and a planned fifth Legoland park all discontinued.

The Toy Market

LEGO’s legendary status at the beginning of 2000 was not up for debate, with its unanimous award as ‘toy of the century’ from three major organisations; The British Association of Toys, Fortune and Forbes. But capitalism cares not for sentiment, and at the start of the new millennium, the physical toy market was contracting, and the conventional wisdom predicted electronic toys, games, and other media would put significant pressure on traditional toys as the 2000s progressed. Kids were getting older faster, it seemed.

Poor Results, Great Brand

However, despite the financial performance, and market challenges, LEGO was still an exceptionally strong brand, with Toy Market Analyst David Leibowitz describing it in The LEGO Group’s Annual Report as being “in a class by itself. LEGO stands for quality, exceptional play value and for capturing the hearts and minds of children around the world. LEGO is to toys what Manchester United is to football.”

Young & Rubicam Brand Survey - Families with Children

Source: The LEGO Group Annual Report, 2003

This immeasurable brand value would perhaps become The LEGO Group’s most important asset in the coming years of financial distress. A high-value brand could act as a financial shield, helping to attract investors or raise additional debt. It could also help accelerate the recovery process, especially for customers with a pre-existing affinity with the brand and who are perhaps just waiting for the right product to rekindle their strong bond. We will come back to this in 2003 and 2004.

Sets of the Year

Image © The Lego Group

In 2000, the New York Times lauded 3409 LEGO Championship Challenge as ‘the most popular LEGO toy this year’ coming with ‘spring-loaded LEGO men, so once complete it becomes a foosball-like game.’ Presumably the continuing antics of Joey and Chandler contributed to this popularity?

Sand Green made one of the strongest colour debuts in LEGO history, with 36 new elements making up almost all the 2,882 pieces in 3450 Statue of Liberty, the largest LEGO set of the year. The other largest sets included 33723 LEGO Mini-Figure, 8458 Silver Champion, 7191 UCS X-Wing Fighter, and 8457 Power Puller.

Image © The Lego Group. Source: LEGO 7191 X-Wing Fighter Instructions.

We Can Fix It

2000 was clearly a challenging year for The LEGO Company, with the loss bringing wider scrutiny, but Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen and Poul Ploughmann were still able to present a positive growth strategy for 2001 based around ‘tapping the market potential in the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, and other European countries where market saturation is far from achieved.’

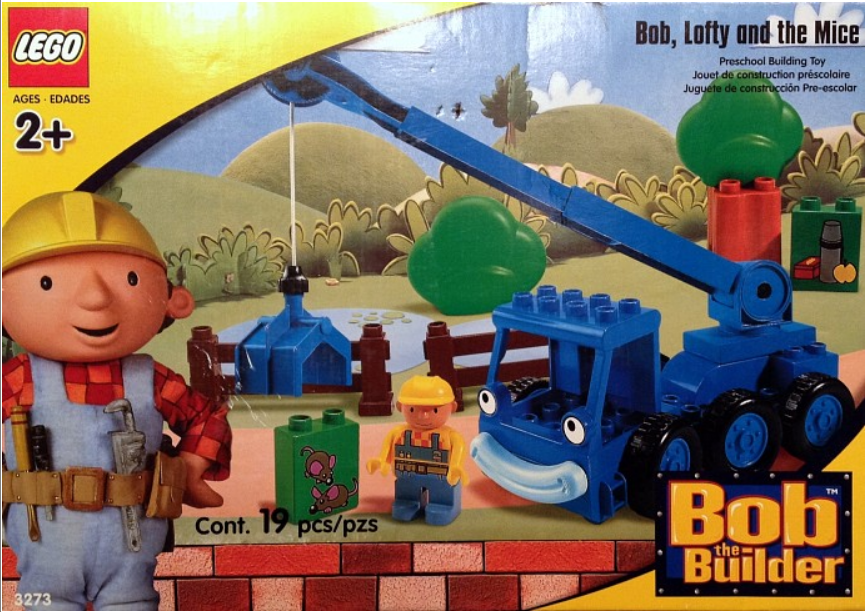

There was also optimism surrounding several themes, including Mindstorms, Technic, Bionicle, Harry Potter, Life on Mars, and Bob the Builder. Their final sign-off in the 2000 Annual Report does not play down the poor result but instead strikes a note of determination, solidarity, and an unwavering belief in The Group’s purpose.

‘We want to assure all LEGO enthusiasts around the world that the LEGO Company is not in danger, despite a difficult financial year. The LEGO brand is as strong as ever. The LEGO Company was built upon a vision that we should nurture the child within every one of us. This is a timeless vision, and we will remain true to it and build our future success upon it.’

2001 - False Dawn

Chapter 2

The White Stripes, White Blood Cells

On 23 October 2001, the very first iPod was released with the ‘mind-blowing’ capacity of 1,000 songs just as the first batch of Millennials were hitting their early-20s and becoming early adopters of this latest tech.

2001 was the year of the debutants The Strokes, and the newly popular White Stripes releasing critically acclaimed ‘Is This It’ and ‘White Blood Cells’… and in the process, they looked cooler than any mortal has a right to.

While Jack Bauer was about to start his hectic work day in 24, Star Trek Enterprise made its television debut and Ricky Gervais launched the British version of The Office, all against the backdrop of the dot-com bubble bursting with one of the casualties being, eToys.com, an online retail company that sold LEGO.

Returning Profits

The LEGO Group returned to profitability in both 2001 and 2002, with a kr.430 million ($52 million) surplus in both years, driven by “higher sales in the American market” during 2021.

The LEGO Group Annual Profit / (Loss), Kr.Billion

Source: The LEGO Group Annual Reports

7435: Tiny's Day and Night Lever, part of the LEGO Explore theme. Image © The Lego Group.

Harry Potter, BIONICLE, Bob the Builder and classic LEGO products were particularly successful themes and “contributed handsomely” to the result, but “products for the youngest age groups found the going particularly difficult.” In 2002, LEGO Explore replaced DUPLO in an attempt to market more effectively to US customers, but the experiment proved unsuccessful, and DUPLO later returned in 2004.

Turnaround?

Business turnarounds are not easy, and clearly, there is no guarantee a company in financial distress can be rescued… just ask Kodak, Blockbuster, Woolworths (UK), and Toys “R” Us. All had failed to adapt to changing technological and consumer trends, and in the late-90’s and early-2000s, The LEGO Group faced similar market challenges.

New York Times, 25 December 2001

Turnaround expert Poul Plougmann was brought in as Chief Operating Officer in 1998. Working closely with CEO Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, he was charged with improving efficiency, reducing complexity and costs, and returning the Company to profit.

John Tagliabue, writing for The New York Times in 2001 stated, “Mr. Plougmann knew the company needed to turn its losses into profits again, so he has moved quickly to shut unprofitable factories and cut the number of employees. Last year, Lego laid off 1,500 mainly white collar workers, eliminating a further 500 at the start of this year.”

The improvement in operational efficiency manifested itself in the 2001 performance, as sales increased 13% from 2020, while operating costs decreased by 3%, delivering an uplift in operating profit of kr.1.5 billion ($180m). Mr Tagliabue continued to write:

“Many of Lego's problems also reflect its own mistakes. In the 1990s Lego enjoyed its greatest success, with a spectacular drive to spread geographically, growing strongly in the United States and developing new markets that opened after the collapse of communism. New products expanded Lego's traditional selection beyond plastic bricks.”

“But the kind of products Lego made transformed the company, too, injecting an element of unease among some Lego veterans. Long a manufacturer of a dizzying array of colorful bricks that required the touch of a child to become a real plaything, Lego started producing more and more ready-to-use figures, like the Star Wars kits it brought out in 1999 under license from Lucasfilm.”

Christmas 2001 Heavyweight Contest

Bratz Dolls dominated Christmas 2001, but the 682-piece 4709 Hogwarts Castle was also a big hit. It was “flying off the shelves as fast as a Quidditch snitch,” and by late November, The New York Times reported “Forget about the Hogwarts Castle from LEGO,” in reference to getting the set in time for Christmas.

4709 Hogwarts Castle Image © The Lego Group.

Harry Potter had obviously got off to a great start, and Star Wars, the other large license, had already rolled out the first two UCS sets in 2000, 7181 Tie Interceptor, and 7191 X-Wing Fighter, which was followed in 2001 with a third ship, 10019 Rebel Blockade Runner.

But one of the most unexpected things I found is the lack of mentions for the new Star Wars and Harry Potter licenses in the general media. Instead, another LEGO product was attracting the majority of the attention during the late-90s and early-2000s period… Mindstorms.

Paranoid Android?

Mindstorms 3800 Ultimate Builders Set released in 2001. Image © The Lego Group.

When a new technology comes along, for a time, it becomes the topic that gets a lot of media attention, with a wide array of topics being viewed through that lens. It happened with the internet, smartphones, social media, and now AI… I reckon if I started a company that claimed to be using AI to help me grow enhanced cabbages, it would get a bit of media attention (I’m not, by the way…yet).

It’s during these technological leaps that companies get nervous, and rightly so, as it could upend their whole business model… as it did for Blackberry who ‘came a cropper’ following the iPhone debut.

In the late 90s, it was electronic toys, and other forms of digital entertainment that were both squeezing the physical toy market and generating significant media interest, with LEGO Mindstorms receiving the attention of The New York Times in 1999 that wrote:

“Created out of Lego blocks and the Lego Mindstorms Robotics Invention System, are proliferating. The $219 set, which contains familiar Lego pieces along with light sensors, motors, touch sensors, gears and a minicomputer ''brick,'' has been an immense success since its introduction last year.”

Mindstorms was also having an impact in Palo Alto - “Mindstorms robots have become techno-toys with as much appeal as the latest Nokia phone or Palm Pilot organizer,” with “one Silicon Valley start-up company, Nuvo Media, had to make an office rule: no Lego play during work hours.”

9748 Droid Developer Kit Image © The Lego Group.

The Coming Storm

The return to profit and the success of products like Mindstorms, Harry Potter, and Bob the Builder had given the company some room for optimism going into 2002. Kjeld and Poul signed off the 2001 results with the following statement:

“We look forward to 2002 in the expectation that the Company will continue its strong, healthy development. Once again, optimism is based on our focus on the market’s most popular products, a series of powerful new launches, and our new-found level of production flexibility. Optimism is encouraged by the positive start we have made to the year – with a heavier retail demand during the first few months of the year than expected. The Parks are also expected to achieve a better result than forecast. Consequently, the result of 2002 is expected to be even better than the result for 2001.”

But alas, it was not to be, and the real beginning of the turnaround had to wait a couple of years. Although the 2002 profit would be in-line with 2001, the 2003 and 2004 results would be the worst in The LEGO Group’s history. But, it was in this intense crucible that The LEGO Group, as we know it today, would begin to be forged.

Source: The LEGO Group Annual Reports

Next Time

This is a planned series of articles over the coming months covering the history of The LEGO Group on a year-by-year basis. In the next article, we’ll begin in 2002, a big year for Star Wars and Harry Potter film releases, and go on to look at the circumstances behind the huge 2003 and 2004 losses.

I’ll also cover other important topics from the time including Legoland Parks, Bionicle, LEGO Brand Stores, and try to understand just how many different moulds and colours were being used in this period.

If there’s anything I’ve missed, or should be looking to highlight in Part 2, it would be great to hear your views. In the meantime, perhaps Bob the Builder himself has the words of wisdom that summarise the next phase in the story…

Can we fix it?… You better believe your [mild expletive] we can!

Image © The Lego Group.

The LEGO Story by Jens Andersen, published 2021 in Danish, and 2022 in English. Available at Amazon.

Essential Reading

As I was drafting this article, my fellow BrickNerds recommended Jens Andersen’s book, “The LEGO Story,” which is a seminal work on the company. It is “the authorised inside story of LEGO” based on “unprecedented access to the company’s archives” including lengthy and fascinating interviews with Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, former president, CEO, and Grandson of LEGO’s founder, Ole Kirk Christiansen.

Are interviewed the author late last year on BrickNerd. I highly recommend the book, and I’d even venture to say it is one of the best and most interesting corporate histories ever committed to paper.

Sources

Notes

All financial information is quoted in Danish Krone, and mostly taken directly from The LEGO Group’s Annual Reports.

Some numbers have been translated into US Dollars using exchange rates from the year the result occurred.

Quotes from Berlingske have been translated from Danish to English using standard online translation tools.

What do you think led to the downfall of LEGO? Let us know in the comments below!

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Charlie Stephens, Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, Andy Price, John A., Lukas Kurth from StoneWars, Wayne Tyler, LeAnna Taylor, Monica Innis, and Dan Church to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.