10 Things I Learned by Building LEGO Skyscrapers

/Best of BrickNerd - Article originally published April 26, 2021.

Building LEGO models of real-life skyscrapers is more complex than it seems. How do you get the right scale, nail the details, support the weight, and make the MOC portable!?

To help answer those questions, we are pleased to feature a guest article from Deep Shen discussing LEGO architecture. Deep’s amazing portfolio of work can be found at Towering Brick Creations, on his Flickr page and on Instagram.

My introduction to LEGO architecture

It was a great honor to meet and talk LEGO with Sean Kenney at Brickfair VA 2019. It was one of his models that inspired me to get started in this hobby.

My name is Deep Shen and my journey to AFOLdom has been a little unusual. Many AFOLs talk about a “dark age” that they emerged from to rediscover their childhood passion for LEGO. In my case, I was completely in the dark about LEGO (having never played with it as a child) until I discovered it as a 40-something dad to a then six-year-old who had just started playing with LEGO. An innocent query from my daughter about building a “really tall” building out of LEGO prompted a Google search that led me to stumble upon the world of AFOLs and all the amazing MOCs out there that have been built out of LEGO.

One model that really grabbed my attention was a model of the Empire State Building built by Sean Kenney. Something about this model appealed to my lifelong fascination with skyscrapers. And as awe-inspiring as this model was, it also looked like something that would not be too difficult for my daughter and I to build (and hopefully we could put our own unique spin on it!). The best part of course, was that we could use the same LEGO pieces that my daughter had been playing with—but we would need many more of them. Armed with a good understanding of scale and proportion that my training as an engineer had provided, I set to work designing my first-ever MOC: a model of the Empire State Building. The rest as they say is... well, let me not get too carried away here!

Anyway, fast forward a few years later and I now have a small portfolio (if you can call it that) of real and digital skyscraper models built using over 100,000 real pieces and many more digital ones. I have been fortunate enough to be able to display my models in a couple of LEGO conventions (pre-COVID of course), and my work has been featured in an assortment of LEGO blogs and other publications. I still consider myself a novice when it comes to LEGO and I have rarely ventured outside my comfort zone of skyscraper models (other than a couple of mosaics I built recently).

But at the same time I think that some of the things I learned by building skyscrapers may be of interest to people looking to build their own LEGO models of skyscrapers or otherwise. Here are 10 things I’ve learned:

1. It's all about the scale

When talking about architecture, you may hear the terms microscale, minifig scale, etc. being thrown around but what do they really mean? If you are trying to represent a real object (say a building) with a LEGO model, the scale is simply the relative size of your model compared to the real thing expressed as a ratio. Minifig scale, which is the size of a minifigure relative to the human it is supposed to represent, is roughly 1/40 (which is to say you need to stack 40 minifigs one on top of the other to reach the height of an average human).

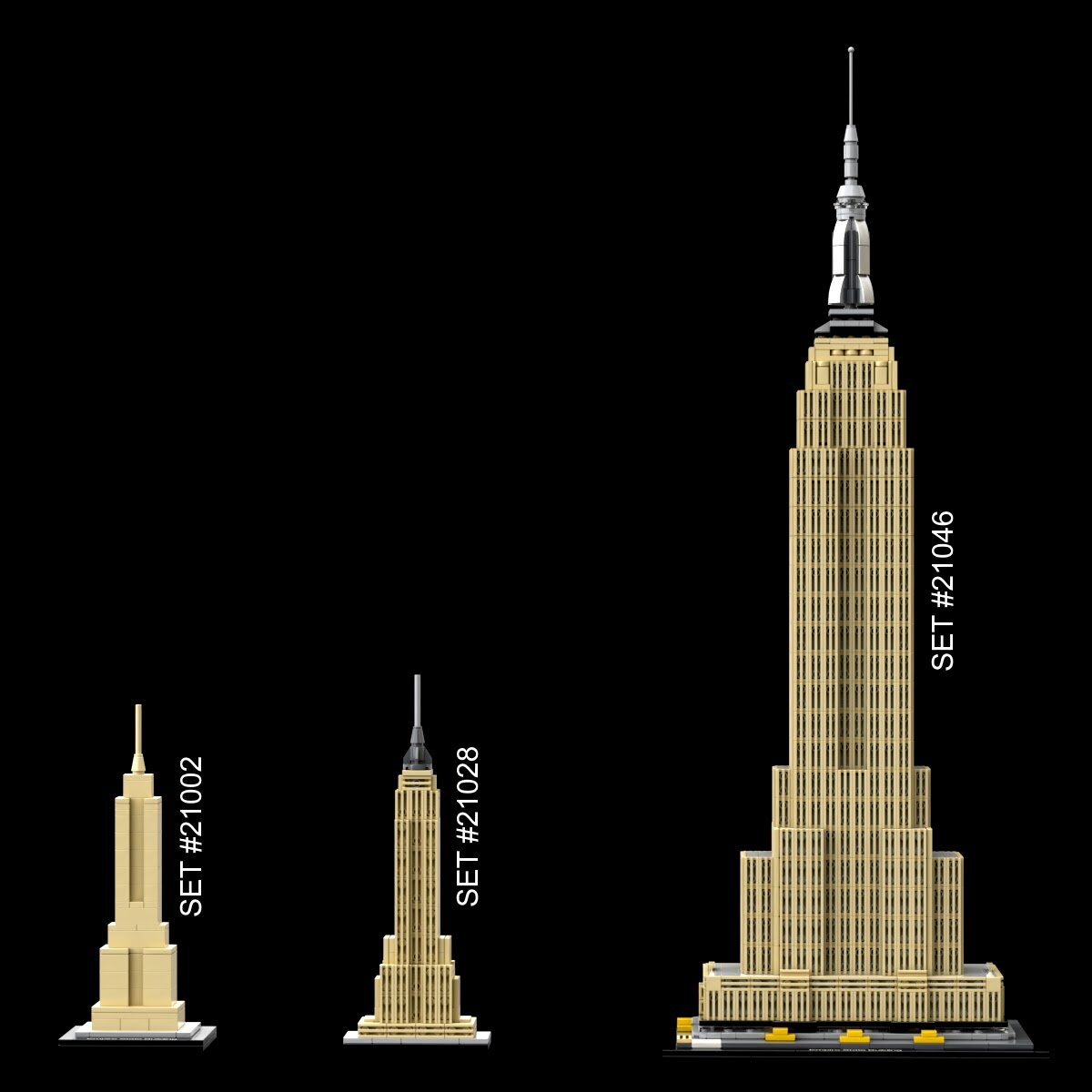

Any scale smaller than that is microscale and it encompasses everything from the tiny scale used for the first official model (set 21002) of the Empire State Building (1/2400) to my six-foot-tall MOC (1/230 scale) and beyond. In fact, a minifig scale version of the Empire State Building would be over 35 feet tall! Anything smaller than that is therefore technically still a microscale model.

As far as I am concerned, picking the right scale is the most important decision you need to make when you are designing a LEGO model of a real building. Of course there is a trade-off involved here. The bigger the scale, the more accurately you can represent all the elements of the original building in your LEGO model. But too large of a scale can also result in a massive, unwieldy model with a prohibitively high piece count and cost.

On the other hand, using too small of a scale can force you to compromise on accuracy (probably more than you would find acceptable). I try to find the sweet spot with my skyscraper models—a scale that is somewhere between the small scale used in the LEGO Architecture series and the huge scale used for the models you would find in a LEGOLAND Miniland. In fact, the scale I pick is usually the smallest one that would allow me to accurately represent the floor count and the window count of the original building (a scale that usually ends up being around 1/200).

People usually ask me if all my skyscraper models have been built to the same scale and the answer is no. I am not a fan of the one-scale-fits-all approach and the compromises that would entail. With each model I try to make it the most accurate representation of the real building that is possible. And so I usually let the building and it’s unique features dictate the scale I end up using for the model.

2. Measure twice, build once

The whole discussion about scale is moot if you don’t have the dimensions of the original building. I am sure many LEGO builders use an “eyeball” approach to figure out how big their model needs to be (in terms of studs and brick heights). They simply look at pictures of the real building and guess. But for every person that manages to pull this off successfully, I am sure there are several others that end up with models that look badly out of proportion compared to the real building.

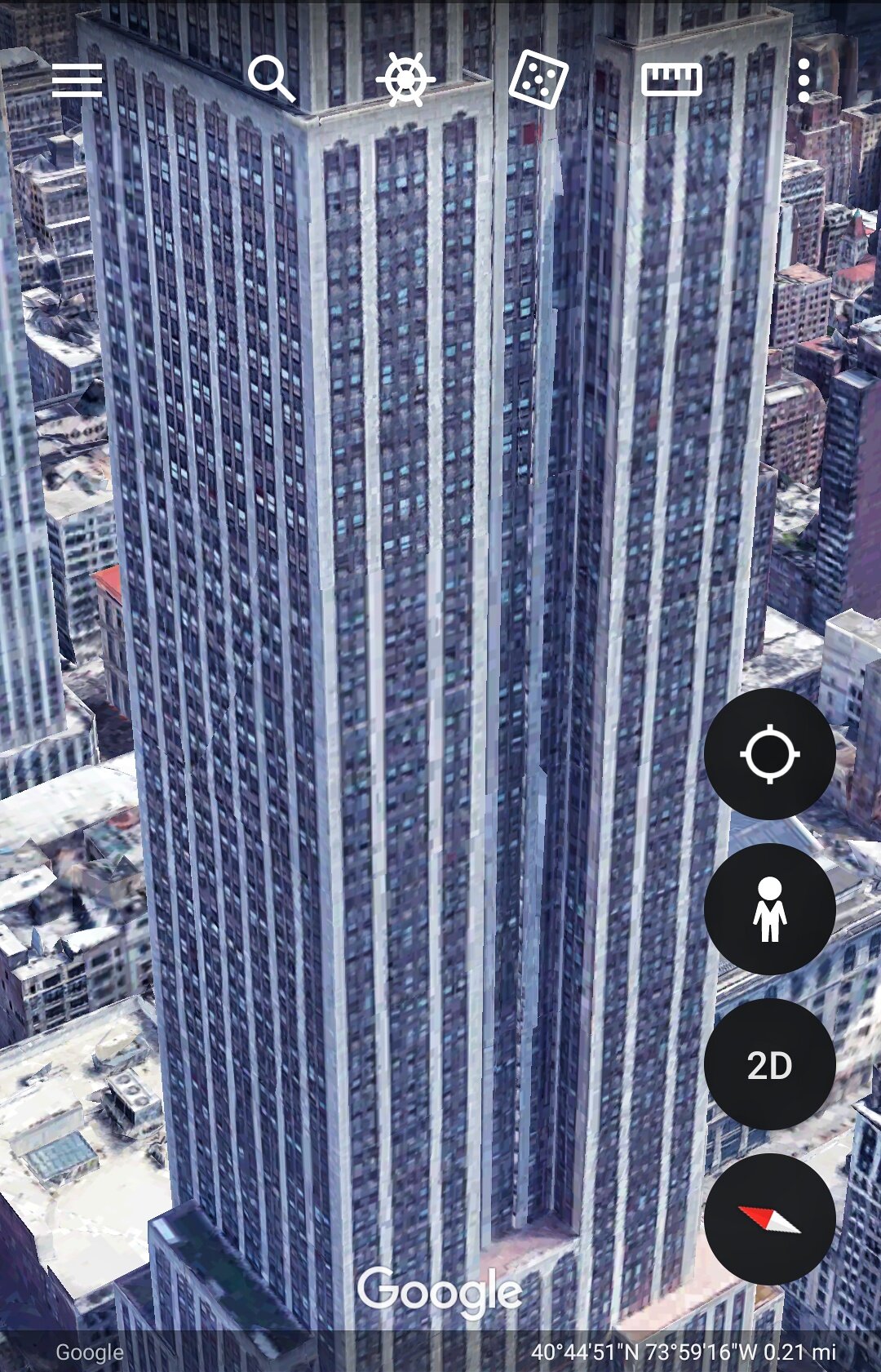

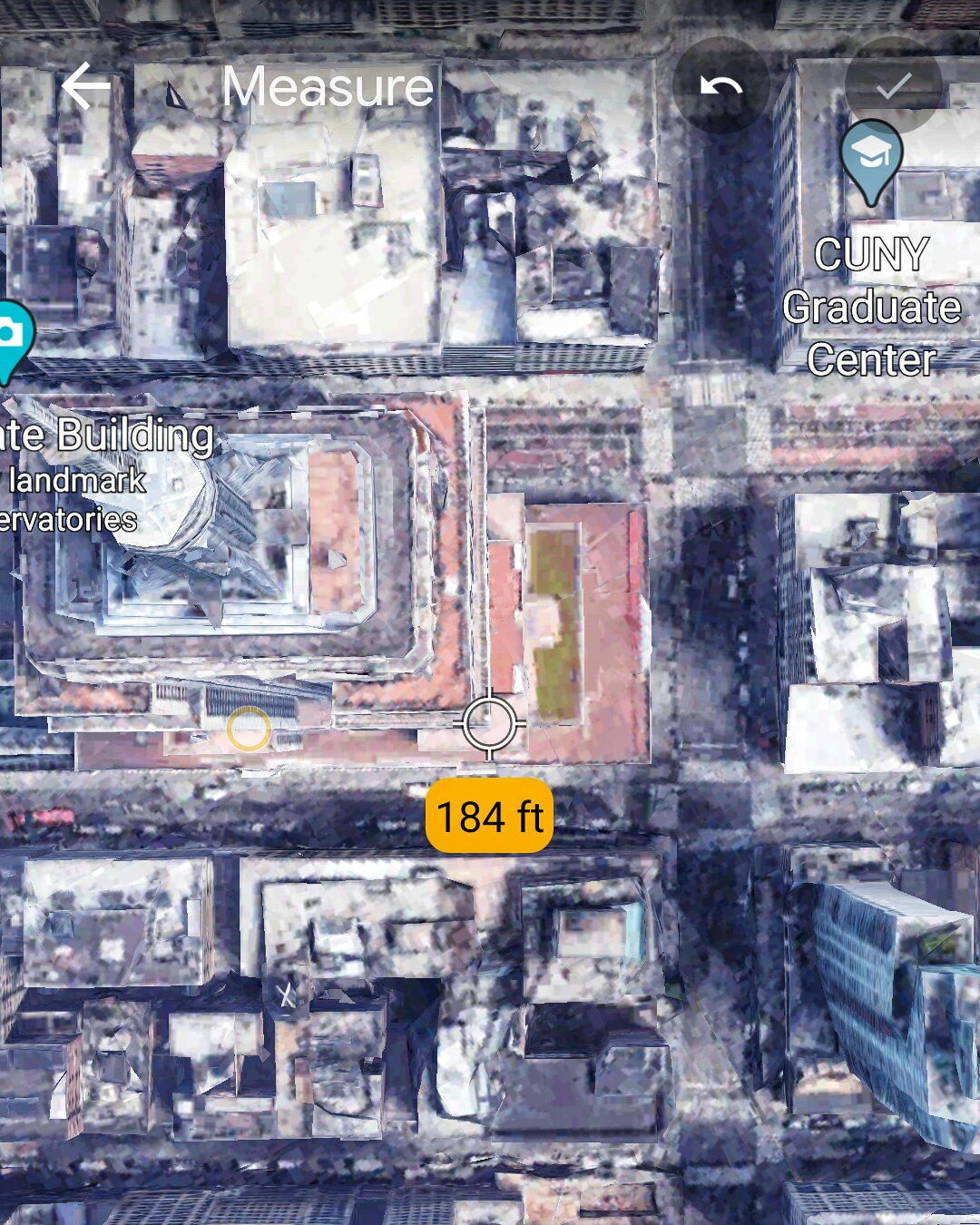

My more rigorous math-based approach requires measurements from the real building. The height of a skyscraper is usually easy to find but the rest of the dimensions are hard to come by, unless you know where to look. For those that are not already aware of this, as long as you can find the building on Google Earth, you can use that program to make very precise measurements.

This is especially useful for buildings like the Empire State Building that taper as they rise and therefore have multiple sections with progressively smaller footprints. Using Google Earth you can zoom into each specific section and measure the horizontal dimensions you need to plan your LEGO model.

It is also not hard to find detailed architectural drawings online for most well-known buildings. Also, if you happen to have a digital version of a picture or drawing of the entire building, you can always start with a dimension that is known (say the height) and get pretty good estimates for the other dimensions by extrapolating using pixel dimensions in the image.

3. Masonry tricks applied to LEGO bricks

What separates modern skyscrapers from the tall buildings that preceded them is the fact that, unlike masonry-built tall buildings, skyscrapers don’t have load-bearing walls. Instead, they have a steel framework to which “curtain walls” made of brick, stone or glass are attached. These exterior walls make up the façade of the building but don’t actually support any weight. My LEGO models of skyscrapers however, are built very much like conventional masonry structures with walls created by stacking bricks. The reason of course, is that it is a lot easier with LEGO to simply stack bricks, than it is to try to mimic the actual internal structure of a real skyscraper.

The art of masonry or laying bricks to build walls has been around since ancient times. One of the most common techniques used while stacking bricks is to create an interlocking “running bond” pattern by staggering the vertical joints between bricks. This helps distribute loads more evenly and creates a more robust structure. The same principle applies to LEGO structures which of course use bricks of a different kind.

It is easy enough to use a running bond pattern and create a plain LEGO wall but a typical skyscraper has walls that are interrupted by windows and accent colors. Also, there are several layers of bricks that need to be stacked vertically (especially for skyscrapers) while ensuring that the whole structure holds together and doesn’t fall apart when you try to move it. On all of my skyscraper models, I have found it necessary to make the walls two studs thick. This allows me to alternate the orientation of the bricks between the layers to create an interlocking structure for each floor (which happens to be two bricks high in my model of the Empire State Building).

Sometimes even this is not enough as you can see from this floor section from the same model. The joints between bricks in the inner and outer layers still line up in a few places and so I need to create two variants of the floor design by offsetting the longer bricks on the inner layer by one stud between the odd and even floors.

4. Just because you don’t see it doesn’t mean it’s not there

Yes, my skyscraper models are hollow for the most part—but that is not to say that there is no need for any internal support structures. For a skyscraper like the Empire State Building that gets narrower as it rises, the weight of each section needs to be supported by the section immediately below it. This is not possible without building some kind of inner walls (hidden from view), especially since the section above is narrower than the one supporting it and it is not possible to simply rest the upper section on the outer walls of the lower section. These inner walls can be somewhat porous with gaps that are bridged over by longer bricks and since they are hidden, you have a lot of flexibility in terms of the pieces you can use.

I typically use regular bricks in the cheapest color I can find, but you can also use any old bricks you have lying around. In some cases it may also be possible to use Duplo bricks which are compatible with regular LEGO bricks. Something I have not tried yet is building an internal framework entirely out of Technic beams but that can possibly cut down the brick count while being just as sturdy as inner walls built out of regular bricks.

5. Divide and conquer

If you are building a skyscraper model that is five or six feet tall, you can’t expect to be able to just pick it up in one piece and move it around (especially if you want to be able to display your model at a LEGO convention). To address this challenge, it helps to build your model in multiple manageable sections. All five of my real models have been built in this manner—the smallest model (the Chrysler Building) has three sections while the biggest one (the Empire State Building) has seven sections.

At the seams between sections I use mostly tiles with a few plates sprinkled in. The plates hold the sections in place when they are stacked together while the tiles minimize the number of connection points between sections. This technique allows the sections to be taken apart easily and put back together as needed.

In the case of my model of 40 Wall Street, the base of the model was too large and heavy and there was no logical place to put in a horizontal seam. I decided to use a vertical seam instead. In this case the two halves of the base are attached together using technic pins.

To be continued…

Even with how nerdy BrickNerd articles can get, this article was originally 6,000 words long. So you’ll have to tune in tomorrow for the next five tips! (Click here for the second half.) But until then, I hope this article can provide just the nudge you need to try building your own LEGO model of a real building (skyscraper or otherwise).

What buildings would you most like to see or build out of LEGO that haven’t been done already? Leave your thoughts in the comments below.

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Charlie Stephens, Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, Andy Price, John A. and Lukas Kurth from StoneWars to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.

![40wall_sections[1].jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51967abae4b0fe8d0161031f/1619382947008-ALIFVA7B4M3DNOZYUBJ0/40wall_sections%5B1%5D.jpeg)