LEGO SNOT: A Short History of SNOT

/BrickNerd is going all in on LEGO SNOT! Get ready to sniff out all the sideways building techniques from beginning to advanced and beyond. This week we are going better and booger than ever, so hold on to your hankies as we explore the intricacies of LEGO SNOT. It is going to be SNOT-acular! Prepare to be blown away!

Eww, SNOT!

SNOT, maybe you’ve heard of it? And no, I don’t mean the slick green stuff that kids leave on their LEGO bricks. If you hang around a group of AFOLs you will hear it used frequently: "I really like how you SNOTted that cliffside!" or "I’m thinking about building the ground with SNOT instead" are phrases you might hear. You might be grossed out at first, but then someone helpful will try to explain what SNOT entails. My name is Oscar Cederwall (sometimes I go by the name o0ger) and I am fascinated by this sticky term, so join me in a deep dive into a pit of SNOT!

What is SNOT?

When AFOLs speak of SNOT we are mostly referencing a technique to build LEGO sideways. SNOT is an abbreviation meaning “Studs Not On Top.” To understand what we mean by “Studs NOT On Top,” we have to understand what it means to build “Studs ON Top.” This is what happens when you start building on a plate and you stack LEGO bricks on top of that plate until you’re finished, from bottom to top. “Studs On Top” is how almost every set was built during the few first decades of LEGO. It could be a house, boat, or car—but everything was built in more or less the same way—from the ground up.

(Images via LEGO and Brickset)

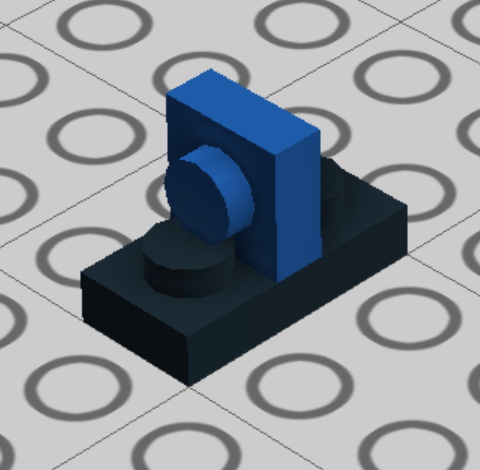

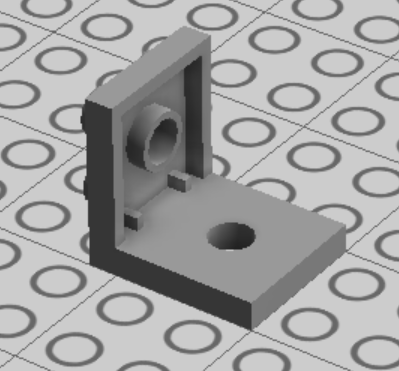

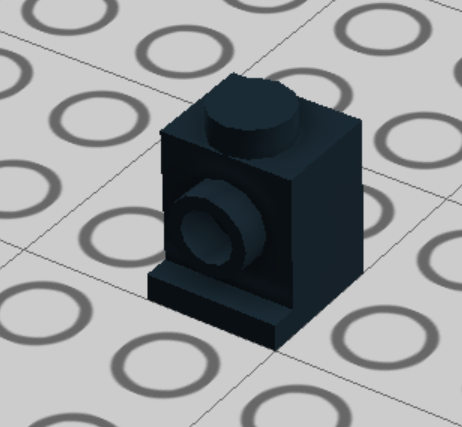

“Studs NOT On Top” in contrast, makes use of LEGO parts that feature studs protruding in different directions other than up. This gives us the ability to build outwards with studs facing sideways. Good, simple examples of this technique include the recent Star Wars busts or any BrickHeadz (though the majority of modern LEGO sets utilize SNOT techniques in some way). Can you see some sideways building in these sets?

A SNOTed surface can still be full of visible studs, so it does not mean “no studs” or “a smooth surface.” SNOT means using all the available parts with studs on the sides, and figuring out how they work together to form a more complex structure.

When I first came across this concept I was directed to a document that I now also want to recommend by Didier Enjary of FreeLUG (French LEGO Users Group) called “The Unofficial LEGO Advanced Building Techniques Guide.” (Fair warning, this document contains many illegal connections, but that is a story for another time!)

Origins of SNOT

I’m not going to lie, it’s hard to track when the term SNOT was used for the first time. According to my research, the earliest reference I could find was in this conversation from LUGNET about useless parts, written by Tom McDonald in 1998:

Like many other abbreviations in the LEGO fan community, when pronounced, the term might translate to something completely different than what it actually means. (Have you heard of BURPs?) But that’s all part of the charm, right?

But what about LEGO itself? LEGO would never officially use the term SNOT, would they? There have been many instances of designers adopting fan terminology (like AFOL), but more often than not, official LEGO communications use the term “sideways building.”

“We’re building sideways!” - (This is a still from LEGO Presents: MICRO SQUARE - Episode 9, 2013)

Though if you use a term enough, it starts to catch on with audiences even broader than the LEGO fan community. The popularization of the building term SNOT seems to have broken into the public knowledge coinciding with the LEGO Masters television competitions (likely because it is so much fun to say and is a memorable name for such a significant technique). Here is a video where designers and judges Jamie Berard and Amy Corbett reference SNOT:

SNOT is official!

For those located where the video is unavailable, here is the key quote from Amy:

Sideways Building

Sideways building is really nothing new in set design though. It has been around since the ’70s and was a way of mounting details on the side of structures. These three examples are from 1973, 1979, and 1980 using three different types of elements to achieve similar results.

My personal view on the progression of SNOT building is that it followed the basic capabilities of the LEGO system. From the start, LEGO bricks were simply building blocks that you could stack on top of each other. When the tubes were introduced in 1958, it gave designers the ability to create more complex structures that would eventually lead to building sideways with the introduction of new elements.

Sideways building was mostly used with the “headlight brick” to build, well, headlights. The technique remained for many years until the middle of the ’00s, where we notice that something started to change. For example, see if you can identify the sideways building in this set from 2006.

If you look at the 7900 Heavy Loader, the entire front of the truck is a SNOT sub-assembly attached to the front of the cab.

Around that same timeframe, we start to see LEGO Star Wars sets getting more complex with SNOT building for added embellishment like in set 7252 Droid Tri-Fighter from 2005.

Presumably, when you want a consumer to recognize a set from a movie, you really need to start thinking more about the overall shaping. This might be the reason why we also started to see a lot more slopes, curved slopes, wedges, and tiles being produced during the same timeframe. I think there was a shift at this point where form became almost more important than function in LEGO sets—and we are still seeing the consequences of that shift today.

The SNOT Cycle

It is my personal belief that the rise of SNOT pieces directly affected the types of elements that are used with them. In my mind, I imagine a development cycle where more SNOT elements gave LEGO designers more possibilities to shape the sets. This, in turn, created a demand for more “shaped sets” requiring more slopes and tiles. That leads to a designer wanting to use slopes and tiles in a new way which creates a demand for more SNOT parts, and the cycle continues. (If anyone has a better theory, let me know in the comments!)

The end result of the SNOT cycle is that we live in an age with more kinds of tiles, slopes, curved slopes and SNOT parts than ever before. This gives consumers beautifully shaped sets and AFOLs and designers alike new ways to build, with the consequence (or benefit depending on how you look at it) that the number of unique elements per set is increasing. Old-school LEGO fans might not like this development, but I, for one, welcome this progression.

So, how do we take advantage of this excess of SNOT? Well, for that you’ll have to wait for my next article showcasing a few ways to use it to great effect. Stay tuned and keep the SNOT coming!

Best of BrickNerd - Article originally published on February 21, 2021.

Do you use the term SNOT or sideways building more? What are some other LEGO acronyms created by fans that you enjoy? Leave your thoughts in the comments below.

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Charlie Stephens, Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, Andy Price, Lukas Kurth from StoneWars, Wayne Tyler, Monica Innis, Dan Church, and Roxanne Baxter to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.