All Roads Lead to Rome: Building the Eternal City, Part I

/As a LEGO builder, what do you do to challenge yourself when you’ve already built an entire country at 1:650 scale, made a detailed replica of First Century Jerusalem, and have models of several of the world’s most famous landmarks on display at a museum? Well, you could always revisit an older project, and expand it to a behemoth piece consisting of a million bricks.

Rocco Buttliere with Phase I of his massive Ancient Rome project. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

Regular BrickNerd readers may recall a previous article of mine, where I described the process of creating an event kit to mark the tenth anniversary of our annual Norwegian AFOL event, På Kloss Hold, in Trondheim. That kit was of course designed by Rocco Buttliere, who happens to be a good friend of mine and therefore my go-to guy for anything microscale.

Rocco has a degree in architecture and since I first met him at Brickworld Chicago in 2015, he’s created one masterpiece more stunning than the other, pretty much all of them in his signature 1:650 scale. We’ve covered several of his builds here at BrickNerd, most recently his First Century Jerusalem diorama back in 2021. His biggest claim to fame is possibly recreating Vatican City—an entire country—but when Rocco revealed his latest project, it became immediately clear that this was a whole different beast than anything he’s done so far.

An attempt to recreate ancient Rome in its entirety is so ambitious that we had to have a chat with Rocco about it, especially since his track record makes actually finishing it a credible feat! Plus, the first phase of the giant diorama was finished a few months ago, and even if it features only a tenth of the total estimated number of LEGO bricks he’ll eventually use, 104,000 bricks is still pretty substantial…

Embarking on the Journey to Rome

BrickNerd: First of all, thanks for sitting down with us again, Rocco! You have built several massive microscale dioramas over the past few years, which I know you consider proof of concept before attempting this vast project. But I have to ask: Why Rome?

Rocco Buttliere: First off, thank you for having me, Are. As if our personal rapport wasn’t reason enough for this story, I’m thrilled to be featured on BrickNerd once more!

It’s fair to say that I never saw Rome coming. The idea of designing a large historical diorama of the ancient city was first put forth back in 2019, at the outset of my years-long collaboration with the Museu da Imaginação in São Paulo. Our initial concepts varied, but we settled on my proposal to capture a large area of the city center at my signature 1:650 scale. The results were both the first times I had ever captured a broad landscape in one go and designed a specific historical period other than present-day.

With the benefit of hindsight, this was a natural progression of the works I had developed to that point. I had previously designed landscapes covering areas of Chicago, London and New York, but the constituent landmarks in each of those were essentially individual projects that grew to encompass broader areas. Rome was the first project I conceived of on a grand scale from the outset, and the first where I was suddenly transported to another time and a different world.

I have always prided myself on having my work firmly planted in reality and exploring the world in which we all live. I was fortunate to visit Rome for the first time shortly after designing the original commission piece back in 2019, and that was it for me. Strolling the streets and seeing works of antiquity alongside—and more often built into—the fabric of a living city set my imagination on fire!

Seeing where we are beside where we’ve been inspires endless fascination. It sparks conversations in which we consider the most critical similarities and differences, and weigh ideas best left discarded and those perhaps worth revisiting. In this way, I found myself seeking not a cheap form of escapism, but a harsh juxtaposition with our modern world; one which is always tempered with just as hard a look in the mirror at our collective heritage.

SPQR, PHASE I, with the Colosseum (right) and Temple of Claudius (left) in the foreground. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

Researching the Eternal City

BN: My wife and I were lucky enough to have you as a tour guide for a day in Rome in November, 2021, less than two months before you announced Phase I. You had told me beforehand that you were doing research on a big project, so I knew why you were there–but how important was it to actually go there and walk the streets for research?

Rome, November 2021. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

RB: I should stress that scouting an area ahead of a specific project-in-mind is not at all the norm! That said, setting out to redesign, rebuild and expand my 4th-century diorama of Ancient Rome for my own gallery, I was in desperate need of some on-the-ground investigations.

My 2019 trip to Rome hit all the right notes: the Colosseum, the Forum Romanum, the Musei Capitolini, Musei Vaticani and so on. Shortly thereafter, I immediately delved into yet larger projects for the São Paulo client, specifically Forbidden City and First Century Jerusalem, the latter of which readers may recall from the 2021 feature. Between these two commission projects, I also created my own Vatican City diorama, which went on to be added to my touring body of work at BrickUniverse events.

I certainly consider each of these post-Rome dioramas as completed works. To be sure, I can’t quite go further than the retaining moat surrounding Forbidden City, the international borders of Vatican City State or the third series of city walls encircling First Century Jerusalem. But as the oft-cited 12th century adage goes, all roads lead men forever to Rome. Along the way and throughout the pandemic, I spent many a waking hour wondering just how much further I could take SPQR:

Should I rebuild the commission diorama as-is?

What if I approached the rebuilding unbound by the strict deadlines of a commission?

Would that gift of more time not require a more carefully nuanced approach, and a thorough redesign?

Could the project be designed to allow for subsequent expansions from the outset?

As soon as it was feasible to do so, I made sure to visit Rome for a second time, eager to refine these ideas with a more thorough examination of the more hidden ancient gems less frequented by the crowds. By that time, though, I had already devised a one-page project brief, fully encapsulating the vision taking shape in my mind’s eye. This was the brief I showed to Are and Karen on their final night in Rome as we were taking in the view of St. Peter’s from a rooftop bar.

Not the worst view from our hotel’s rooftop bar, right?

Separating Fiction from Fact

BN: You mention a map from 1901, a physical model from 1971, a couple of books and an ongoing 3D model project as reference sources and inspiration, but I can also see from your in-progress shots that you’ve used YouTube videos and pictures. Is it easy to find and decide what to use for reference, and how much of it is trustworthy?

Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

RB: Trustworthiness is one of the most salient questions of our time. I have always relied on archaeological information to start, but have never shied away from presenting my own interpretations at a confluence of various—and conflicting— accounts. A perfect case in point would be my interpretation of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem (right). Archaeology is, after all, much like any other scientific approach to studying the past and, therefore, scarcely ever fully proven. More often it is disproven, a fact that is all too overlooked by the mainstream of any given period. Whether it be the visceral reactions to Sautuola’s 19th century discovery of the palaeolithic cave paintings at Altamira, or the profoundly consequential and presently-being-rewritten chapter of human history during the Younger Dryas.

Examples of using YouTube videos as reference sources. Photos © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

The point here is that I am ever wary of narratives which claim to be authoritative or definitive when it comes to these sciences. This is, in part, something I first considered from reading Mary Beard’s SPQR, in which she is careful to emphasize just how much is open to interpretation and how our understanding of the past is predominantly shaped by the breadth of our knowledge at the specific point in time in which we view it. It’s a classic Schrodinger’s Cat scenario, wherein the view of Ancient Rome in the 19th century, for example, is probably best encapsulated by Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Beard’s SPQR, on the other hand, fastidiously explores earlier historical territory with far greater nuance as befits our current understanding and lack thereof.

The specific sources on which I rely, like you mentioned, are quite varied in time and format:

The 1901 Forma Urbis Romae by Rodolfo Lanciani superimposes ancient plans and archaeological information over a modern map of Rome. The vector drawing is free to download and forms the basis of my comprehensive AutoCAD map, to which I constantly refer when designing and on which I continually draft new overlays and construction lines.

Detail from the Plastico di Roma Imperiale. Image via Wikipedia, credit Jean-Pierre Dalbéra.

The Plastico di Roma Imperiale is a physical model by sculptor Italo Gismondi which has stood as the most enduringly iconic physical representation of the ancient city; that is, until the Museum of Roman Civilization where it is housed was shuttered in 2014. This piece—or should I say the low-resolution images we have of it—is indispensable when it comes to visualizing a specific area in context, but I would argue is fundamentally flawed in both its sterility and the permanence of its installation.

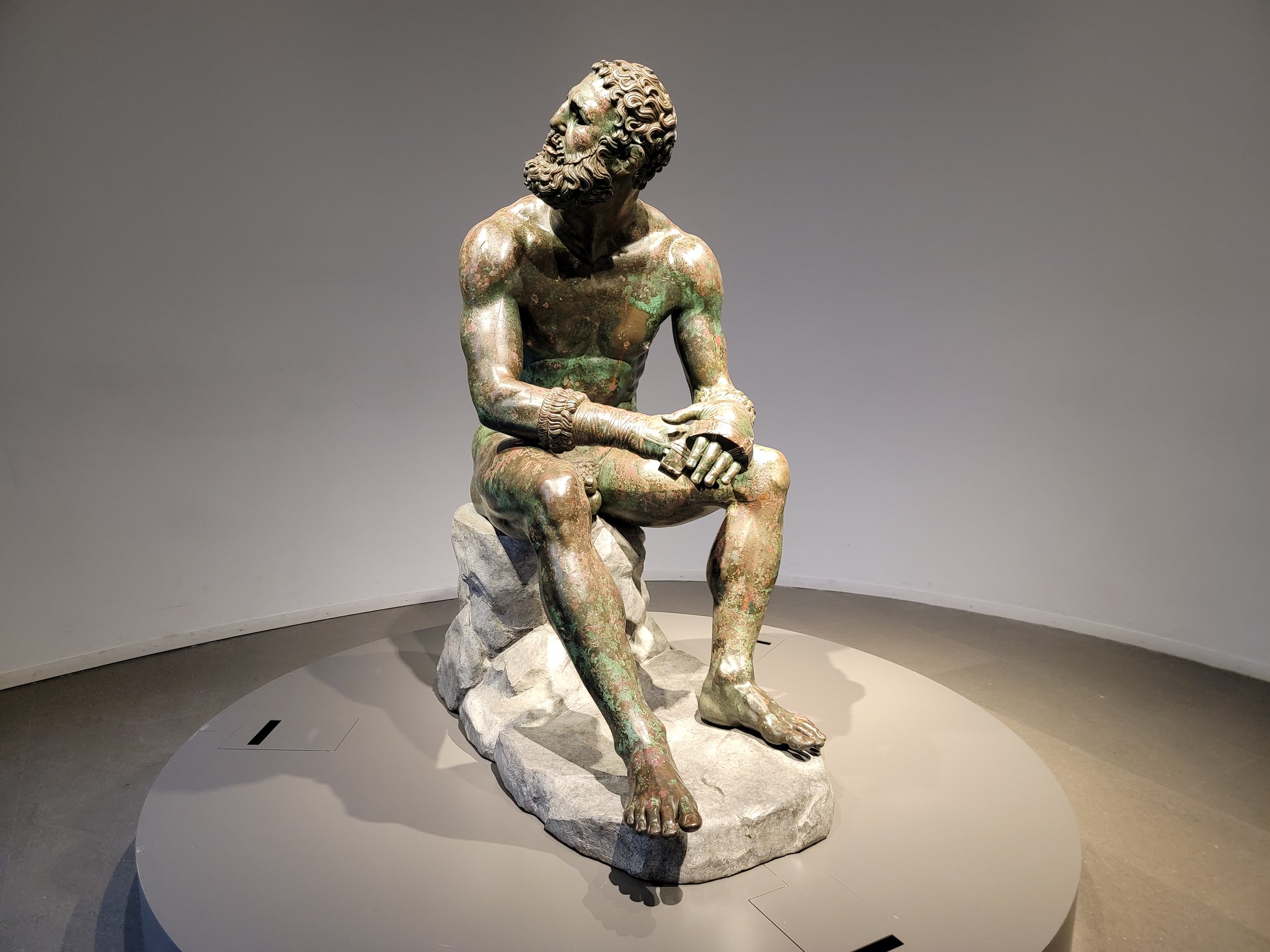

My primary reference throughout the design + build process thus far has, by far and away, been the two-volume Atlas of Ancient Rome by Andrea Carandini et al. I am always careful to remind myself that this atlas is just the latest (2017) compilation of comprehensive topographical information on Ancient Rome, of which there have been many over the decades. I do, however, take equal care not to sell things short as its exhaustiveness stretches far beyond the strictly architectural-archaeological and layers with it all the known historical information pertaining to each and every specific topographical unit. What’s more, the atlas includes countless callouts depicting on-the-ground evidence, cultural iconography in the form of coins and inscriptions, as well as artifact provenance; i.e. showing the famed bronze Boxer (below left) and Hellenistic Prince (below right) sculptures in context with the reconstructions of the Baths of Constantine where they were unearthed before eventually making their way to the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme where I first saw them in 2021.

Off the Grid

BN: Building models of actual locations, especially of a geographically larger nature, means that it is necessary to go off the regular 90-degree LEGO grid. This is of course nothing new to you, you’ve been doing this since your work on downtown Chicago back when I first met you almost ten years ago, but how do you decide how to divide your dioramas into sections, and how much trial and error goes into the process of aligning different sections and attaching odd-angled sections to each other?

The Chicago North Loop layout in all its detailed glory. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

Chicago Angles. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

RB: Chicago is where it all started for me! There are bends in the Windy City grid following the Chicago River which were often accommodated by reciprocal angles in wedge plates (see the image on the right). The idea there was that any angled boundary along a seam of matching wedge plates can be boxed within the surrounding regular grid on all sides using the same wedge plates, no matter the orientation. The buildings were then placed atop these subsections, requiring quite a bit of dismantling and strategic repacking after every exhibition.

Forum Romanum. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

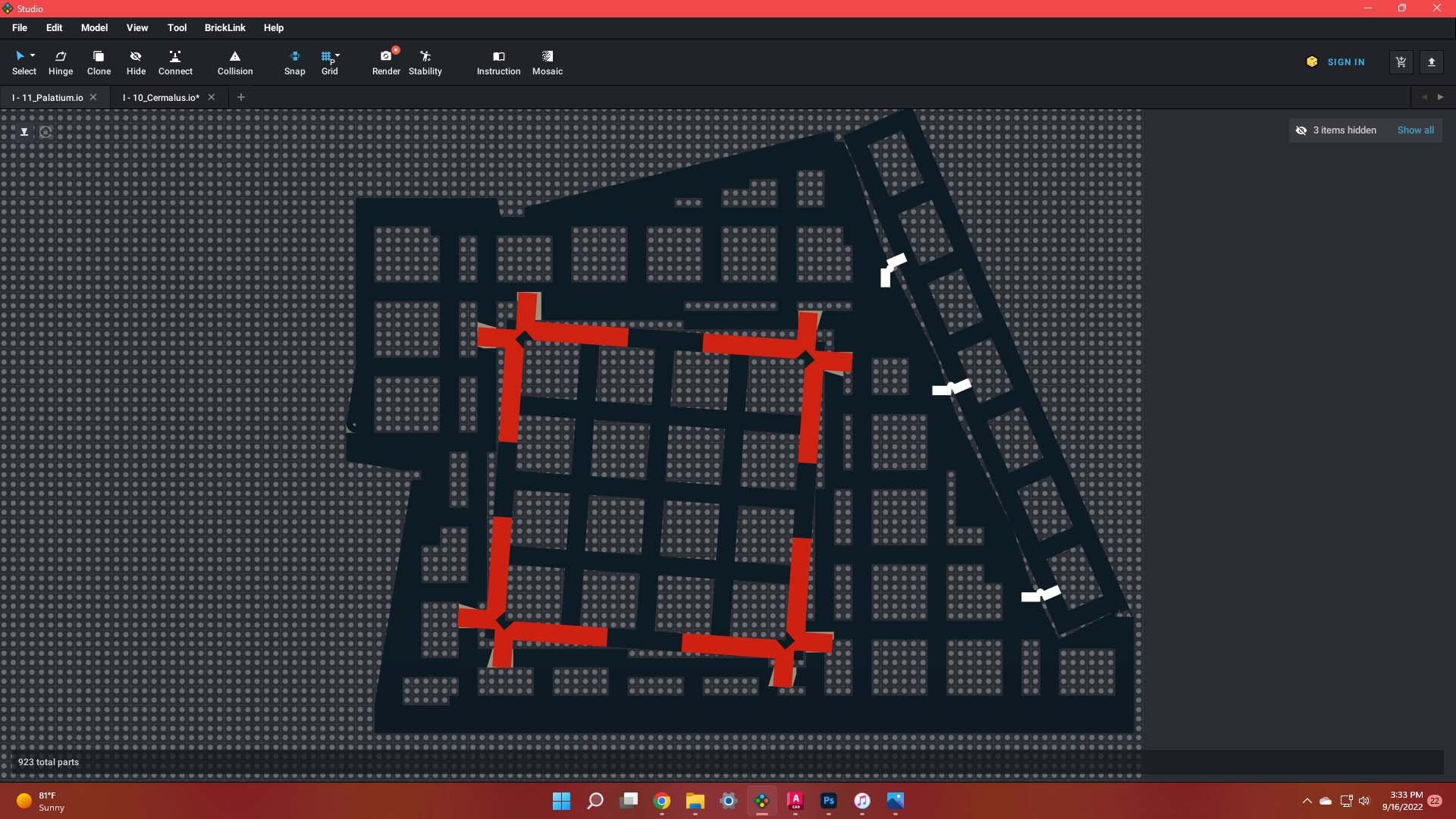

In the years since these crucial first attempts at integrating irregular angles, you could safely say things have become considerably more complex! The modular approach remains, but my modus operandi is far more granular in the sense that all grid adjustments are taken on a case-by-case basis. For instance, the Forum Romanum in SPQR – Phase I is rotated 14° relative to the regular grid of the Velabrum area (the sprawling domūs and insulae between the Capitoline and Palatine Hills). Along its borders, the Forum subsection meets all adjacent subsections differently. Some borders run parallel at the same angle; others match the angle, but are reoriented to another angle further afield; while one seam is so slightly angled at a further 4°, it is simply covered at street level with wedge plates.

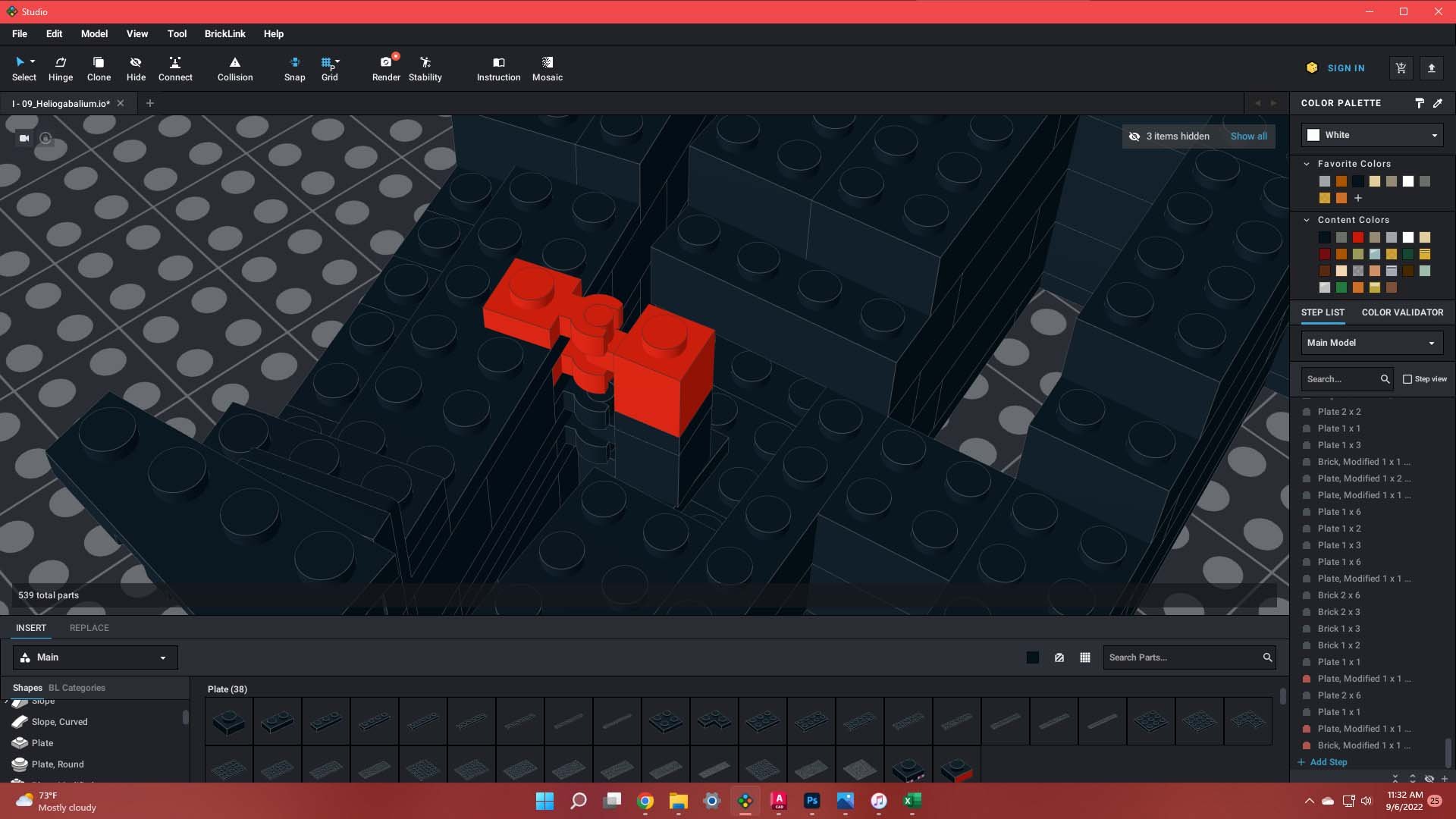

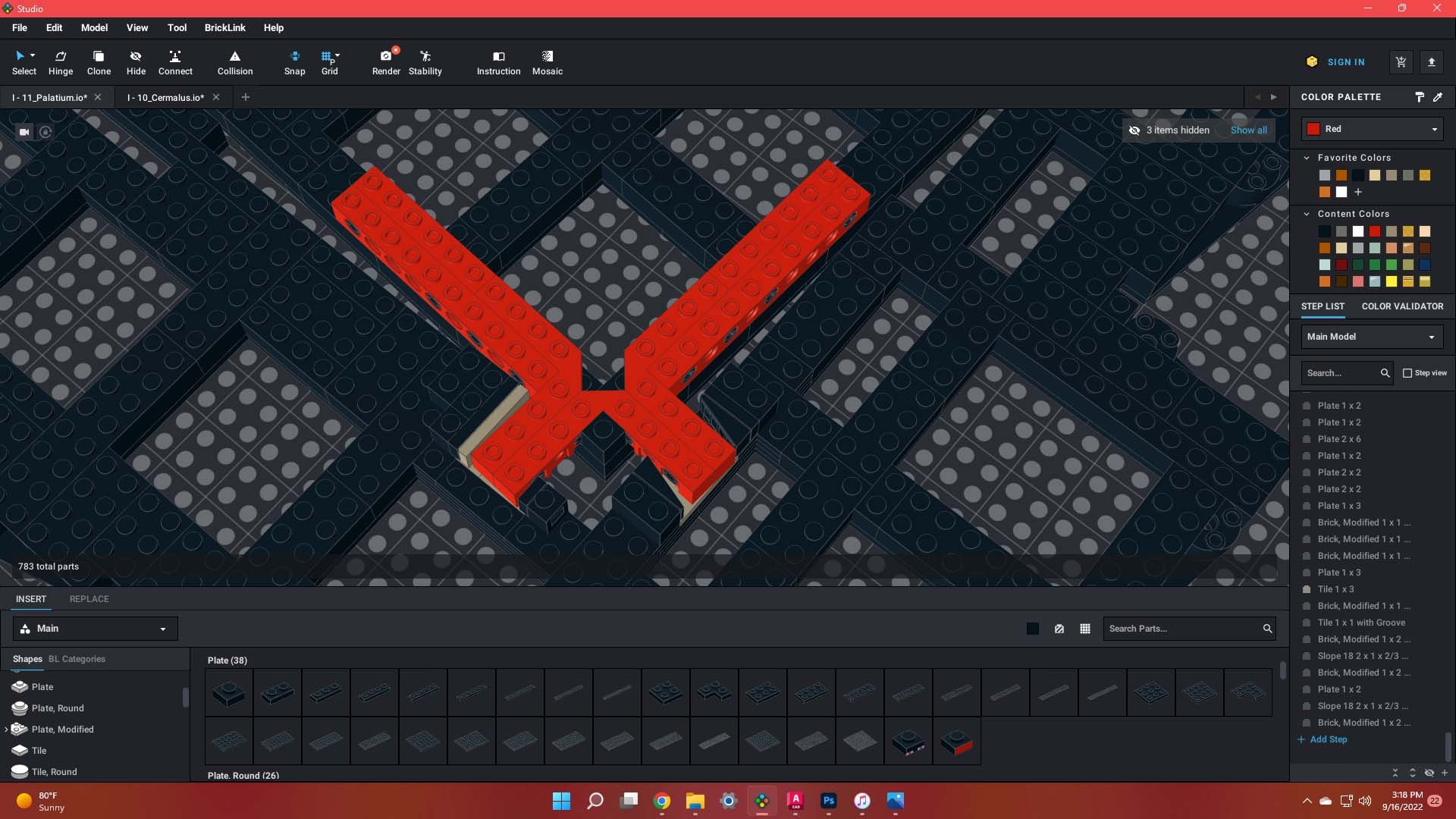

As important as the substructure alignments are, they are often only designed to adhere to the majority of structures at street level. In the case of the Forum, the complexities are further compounded by the fact that several buildings are not axially aligned. My typical solution for this is to place the building footprint atop a single stud, rotated at the correct angle. Next, I methodically look for possible stud alignments beneath at half-stud increments, as illustrated below. Perhaps only one or two studs - but as many as four to six in some cases – can be found, allowing the building above to be attached at fixed angles. This surface level approach has become so ubiquitous, in fact, I have a separate “Misc.” Stud.io file in which I save the frameworks for some of the more stable underlying stud alignments; typically those at angles shared by wedge plates and those with two or more connection points.

Different Angles of Attack

BN: I’m going to have to ask you one more angle-related question. In a corner of one of the Forum Romanum buildings, you’ve got a cheese grater slope connecting two brackets that are flipped 90 degrees. Then there’s a skeleton arm attaching the cheese grater slope to a 1x1 brick with handle–but to get the angle exactly right, that 1x1 brick has to be rotated just a little bit. And to accommodate that, the adjacent bricks must be a 1x2 log brick and a 2x2 round brick. Then plates are added on top, and the wedge plate fits perfectly. This is mind-boggling to me. How much time does it take to come up with something like that? Or are most of these things solvable with techniques you’ve used many times before?

RB: Ah, that would be the angled façade of the Basilica Paulli / Aemelia. And it’s one of my favorite unseen moments of Phase I! This technique was developed specifically for this Basilica. My first step in its development was to decide on using the 2x3 wedge plate to match the angle on the roof above, as you pointed out. Of course, the immediate challenge from there was deciding how to accommodate an angled portion of façade while also maintaining the established techniques of the other frontages of the basilica.

The simplest solution for attaching angled sub-assemblies to a larger structure would have been to use tile clips. The trouble there, though, is spanning the distance from the inward-facing studs to the interior bricks of the structure. There really aren’t any elements with perpendicular bar segments on either end; but there are plenty of robot / skeleton arms with clips at either end!

Now, I had only just discovered that a minifigure hand is capable of clasping one of the louvers of a 1x2 cheese grater slope. For all intents and purposes, the minifig hand is a variation on a clip. While this clip would serve well as a pair of pediment acroteria on other structures, I was sure I could use a robot arm to clip onto a louver of the slope and connect it to a bar within the structure. (You can see how the technique works in this Instagram reel!)

It takes planning to get something like this sit so flush… but oh, how satisfying! Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

Sequencing any such techniques in hindsight always belies the fact none of the development therein was a foregone conclusion. I recently heard a guest on a podcast—can’t remember who and can’t recall on which podcast—explain that when you show up and engage in the creative process, the muse will also show up, more often than not. I think that rings true in my experience. It’s an act of faith in yourself just to show up at the studio desk and appreciate that there are always unanswered questions that are bound to be solved with the right amount of belief, experience and chance.

A Digital Approach to Ancient Architecture

BN: I find that building off the regular LEGO grid is challenging when designing digitally, but yet you seem to be using Stud.io for almost all your design work. I can see how it must be fascinating to see such a big project grow out of the screen and onto the build table, but do you perhaps do physical building in parallel with the digital design, to test the tolerances of the bricks?

RB: It's funny you mention the fascination of a project growing out of the screen and onto the table in physical bricks. That process took nearly a year, and long before that, it spent years in my head. On top of that, just imagine the completed diorama also needing to be photographed, filmed, packed and shipped before making its public debut! There’s joy in it all, to be sure. But it’s also quite terrifying along the way.

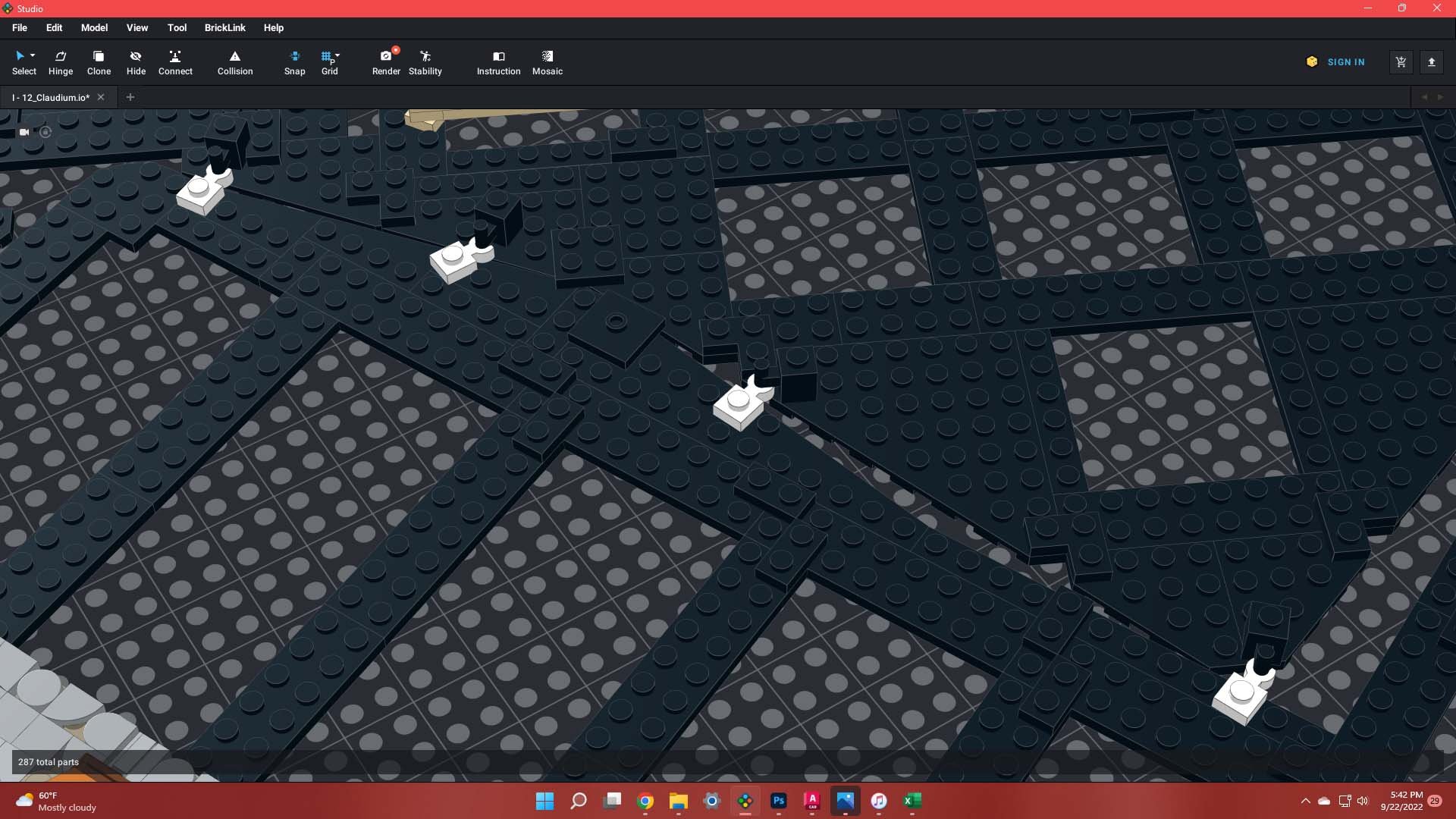

the Temple of Claudius in stud.io. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

There’s really no better phrase for this dichotomy than Agony & Ecstasy. You wouldn’t need to have read Irving Stone’s fictional Michelangelo biography of the same name to know just how all-consuming the creative process can be. I’m careful to always temper my creative process with everyday tasks such as exercising, cooking, reading and the like. I’ve learned to accept the finiteness of a single day and am glad to have left the senselessness of college all-nighters behind! There’s also such a cultural tendency toward an unhealthy amount of work at the expense of all else, which I reject out of hand.

the Temple of Claudius in bricks. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

But I digress; the important thing is to recognize and utilize the tools at your disposal as effectively as possible. As you said, digital design is a great place to start—especially so with the small scale at which I operate, where far fewer bricks count for far more detail. There were several times during the design process of SPQR, however, where an idea could only be tested physically.

The aforementioned acroteria are a perfect example. I could have used the microfig statuette / trophy element as a stand-in for every notable statue, but that would have ignored the critical cultural motifs behind, for instance, the representation of Nike, the goddess of Victory whose golden image topped temples and honorary columns beyond count. I tried several digital variations attempting to represent her winged likeness:

Trying to figure out how to recreate the statues of Nike at 1:650 scale. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

… but it was a moment of table-scrap building that revealed the answer after probably an hour of unsuccessful digital iteration. The rounded end of the wand element is about the same size as the head of the statuette, so that had me thinking along anthropomorphic lines when the idea of minifigure hands as wings suddenly popped into my head. Minifigure hands have the added peculiarity of attaching at a non-perpendicular angle. So, I clasped a pair around the shaft of a wand element, with the angle pointing upward to represent unfurled wings (as demonstrated in this Instagram reel).

That was a moment which spoke to clarity of purpose for me! And the fact that the clasping of the hand around the wand shaft works so well is a testament to the idea that answers will come given enough time and focus. I keep a small bag of extra golden wands and hands with the piece at every show, but haven’t yet needed to fix or replace a single tiny Victory!

Victory! Recreated with minifig wands and hands. Photo © Rocco Buttliere, MMXXIII

Well, the doctor says you shouldn’t stare at the screen for too long at a time without a break—or was that my parents? I can’t remember. Anyway, we’ll leave Rome there for today, but stay tuned for Part II of All Roads Lead to Rome, coming soon to BrickNerd—in which Rocco talks about details, references Elton John, discusses NPU (there’s a lot of it in SPQR) and the cost of building something like this… and lets us know where he’s headed with Phase II!

Best of BrickNerd - Article originally published June 21, 2023.

Have you ever been to Rome? When in Rome, did you make a Promise, or do what the Romans do? And did really all roads lead you there? Let us know in the comments below!

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Charlie Stephens, Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, Andy Price, Lukas Kurth from StoneWars, Wayne Tyler, Monica Innis, Dan Church, and Roxanne Baxter to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.